(This is part 1 of my response to Elle Griffin’s open question ‘how can cities be designed for the benefit of their inhabitants?’)

The Great Fire of London of 1666 was one of the greatest disasters to ever befall a city. It was also an explosion of urban creativity.

It seems horrendous to dwell on the positive effects of a disaster that killed so many people, but in the years after a new kind of city rose from the ashes of London.

The fire changed the height buildings in London could be built to, standardised the usage of brick and stone rather than wood, and reinvented London’s plumbing and sewer system: it also birthed the Fire Brigade, the concept of insurance, and the version of St Paul’s cathedral that still stands today.

Necessity is the mother of invention, and The Great Fire of London was the mother of all disasters. Right now, the twin shocks of Covid and climate change are forcing us to rethink what a city can and should be, and how we make them more equal and sustainable. This moment is frightening, but it’s also pivotal, and as William Macaskill points out1, right now we are the ancients - we have the chance to embed a new set of values into the blueprint of our future cities.

So the opportunities are big and yes, potentially utopian - but before we answer that, let’s start with the most basic question: what is a city?

Or, as someone smarter than me put it:

“What is the city but the people?” - William Shakespeare, 1608

At the moment cities are just very large collections of human inhabitants. And this sets two broad ways of thinking about what a city is in reality and the popular imagination.

So let’s start with the good stuff, shall we?

The city is the best of humanity

The city is an incubator of ideas and creativity, a platform for human ingenuity, petri dish of culture and commerce, crucible of democracy and new political ideas, driver of economic and technological progress.

Cities are where the action is, where the magic happens, where ideas go turbo. And all of these positive effects multiply as they grow. The bigger the city, the better:

They’re also just great places to get laid, find love, make friends, get lost, get wasted, and have excellent meals. The creativity in cities doesn’t just occur in the centres either, but often on the margins: I’ve been enjoying reading London Feeds Itself and its central thesis that all of London’s best food is found in out-of-the-way and unglamorous areas rather than in the fancy restaurants in zones 1 & 2.

The kinetic and creative energy of cities can’t even be constrained by national boundaries. There are cities across the world that already spill over international borders, with examples of transnational cities being the San Diego-Tijuana corridor between the US & Mexico, and Kinshasa-Brazzaville between the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Republic of Congo. Cities are profuse and profane, wild and creative: they want to spill over all boundaries and overflow with creativity.

Humans have created no substitute for what cities do, and in China they’re trying to supercharge their creative and commercial potential by hooking multiple cities together into densely-networked megaclusters using high-speed rail and internet.

If humanity is to continue to flourish, cities are where it will happen. But let’s look at the other side of this, which is less rosy.

The city is a dystopian hellscape

As Italo Calvino puts it in uber-city-text Invisible Cities, cities are ‘the inferno of the living’

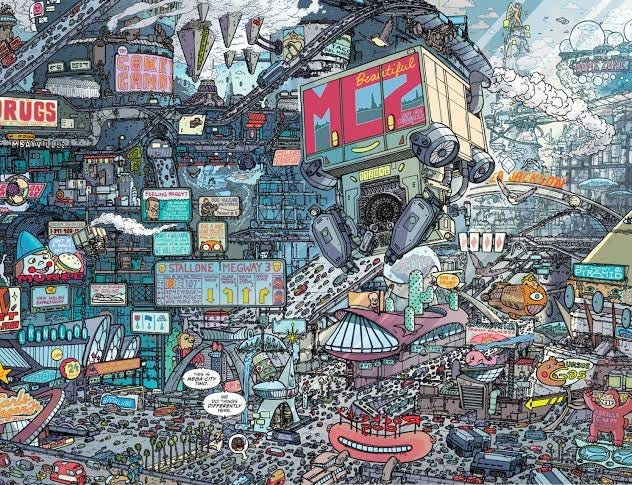

The city is a node of colonial exploitation stripping wealth from far flung territories and peoples, a cancer on the planet feeding on the earth’s resources, a vertical machine that strips us of our humanity, a giant surveillance apparatus that it is impossible to escape, and a landscape across which radical inequalities are enacted and enforced.

If you want a glimpse of the infernal city, look at the favelas of Rio, the slums of Mumbai, the arsenal of exclusion deployed in many cities to prevent members of the public from accessing public space, and the appalling homelessness in the wealthiest cities in the wealthiest state in the wealthiest country in the world (Los Angeles and San Francisco),

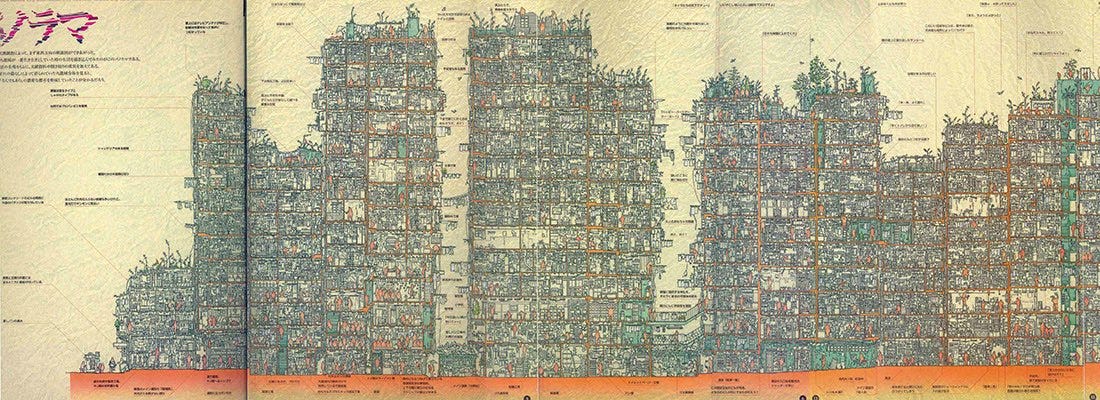

Cities have us racing headlong towards the society depicted in Stephen Graham’s Vertical, J.G. Ballard’s High Rise, or a nightmarish modern version of Kowloon Walled City.

The infernal city is mechanised and industrial, overlaid with digital media and surveillance infrastructure, a place where your position on its vertical hierarchy dictates the life that you live and the urban arsenal of exclusion ensures that certain areas are not public space.

You already know what it looks like, because you’ve seen it in every movie, comic book, game and show from Judge Dredd’s Mega-City One through Blade Runner, Cyberpunk 2077’s Night City, and the comic book Transmetropolitan.

It gets worse: the infernal city is a dense nexus of polluted air, water and land with roots miles deep criss-crossed with piping, wires, cables, industrial deposits, and human effluent. Their growth correlates with human suffering, planetary destruction and a warming climate.

“About 25% of the total climate problem is directly linked to the construction, operation and siting of our buildings. Probably more than that when you include a lot of the transportation choices we’re not making because of bad land use and built environments” - Jonathan Foley, speaking on Disco’s Practical Utopias course

It feels like our ideas of the city are trapped between these two irreconcilable facts: the city is a launchpad for the best of humanity, but we’re burning the planet and a lot of its inhabitants to achieve lift-off. Continuing on this trajectory is likely to make cities the last redoubt of human society on a wasted earth.

This ruined future already looms large in our collective cultural imagination. We’re accustomed to seeing the ultimate expression of a post-human future as cities taken back by nature: the roads overgrown, the homes crumbling, the people long gone. The Tate Britain once ran an exhibition called Ruin Lust exclusively devoted to artistic works of desolated cities & buildings being consumed by nature.

“Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Ozymandias

But what hope does that give the human race other than to proactively nuke every city on earth, and send us all back to some Riddley-Walker-esque pre-modern society?

“Seek and learn to recognise who and what, in the midst of the inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space” - Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

Part of the problem of the urban binary we’re trapped in is that when we talk about their inhabitants, we always mean lots of humans.

But in his book The Wild Places, Robert Macfarlane travels the length and breadth of the UK looking for the last remaining genuinely wild places, before arriving at the conclusion that the idea that ‘human’ and ‘wild’ can be partitioned is ridiculous. Humans and wildness go together, and they have co-existed everywhere for thousands of years.

And if that’s the case, why can’t that be the case in our future cities? Can we rewild our cities?

Cities are wild organisms

Cities aren’t just built, they are grown. What makes cities great is that they’re the closest thing humanity has come to recreating the messy, decentralised and chaotic abundance of nature. Attempts to plan them have failed since Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs battle for the soul of New York, and if you want an example of how dead or sterile over-planned development of cities can make them, look at Neom or Milton Keynes.

Attempting to organise cities into neat zones leads to single-use space, which is often dead space. Mixed-use space gives European cities their vibrancy and sense of aliveness. Everything is happening everywhere all at once. They’re not neatly organised, they’re wild.

At a macro level, we try to constrain and over-plan cities in the belief that it makes them better, but it doesn’t always work. In London a plethora of protected building categories and matrix of different planning laws shows the limits of this approach. Over-planning leads to shrinking homes and unaffordable housing, partly because we’re put an artificial green ring around cities that can’t be used as living space - as Matt Yglesias has pointed out. This is falsely presented as a conservation decision - I think people like the idea of a protected Eden around cities - but the reality is motorways and golf courses not some sort of blessed rural Albion.

There may be far better ways to tap into the power of cities whilst also nurturing the environment than just sticking a protected ring of greenfield outside them. Most pertinently, by bringing the green and nature into the cities - or just releasing what’s already there.

Cities are full of wild life

Most of the moments of greatest pleasure that I find living in London are those where you become aware of the natural world inter-woven with human life: this could be parakeets nesting in the tree at the end of your garden, foxes shitting on your doorstep, or swimming in open water just a mile from your house.

There is already a wild city underneath and alongside the cities in which we live, we have just historically destroyed or repressed it to make way for human inhabitants and infrastructure. We would do well to let the flourish, because we will too.

We have a growing understanding of the psychological effects of access to nature, with a recent survey by Natural England2 and more by The Good Life 2030 project3 nailing the simple truth that everyone needs nature: it is important for mental health, the wellbeing of children, and human flourishing. If you need anecdotal proof of this, ask anyone who had a garden or local park what it meant to them during Covid lockdown. Now ask someone who didn't have one what they missed.

At the moment we interpret as this meaning parks and gardens, but we can aim for more than that.

Reconciling natural wildness and cities might seem impossible, until you read about the incredible work being done in the Hudson Bay in New York. Serious civic engagement and long-term thinking has led to a harbour cleaner than it has been in 100 years. The Billion Oyster Project are 100 million oysters into their 2035 goal to return a billion oysters to the river, and the result is oyster reefs that are cleaning the infamously filthy harbour water a little more each day.

As a result, marine life has returned: humpback whales, fin whales and right whales are also coming back, along with bottlenose dolphins, spinner and hammerhead sharks, seals, blue crabs and seahorses.4 If NYC can do this, why not elsewhere?

This isn’t just about wildlife: the unique and not always hospitable weather of cities - hotter, more overcast, and drier than the countryside - also generates its own unique species of plant.

“Another category of urban flora, beyond the managed gardens and the wild invaders of our roads. It is a hidden, potential flora, an idea of a forest, not in competition with the city but existing alongside it, patiently, waiting to become manifest’ - Daniel Mason, City of Seeds

There is a far wilder city being trapped under the dirty concrete and steel lid of our current urban landscape, and one way to make our cities better might be to stop repressing it and let it out.

Cities with more wild life would also be more equal: Common green space and wildlife creates shared public spaces that people are forced to inhabit, which is good for civic life and bonding.

Ideas like Miyawaki Forests show it’s possible to create small urban forests interspersed with buildings and property in spaces as small as three square metres, with positive climate impacts and more liveable cities as a result. London’s first, in Chelsea, is a year into its growth. You could fit a lot of these mini-forests into a city with the willingness to do it.

A rewilded city where we try and bring nature into the urban fabric might involve everything from vertical farms and rooftop gardens, to using wood rather than concrete in our buildings, to moonshot projects like the Hudson Bay effort to restore a more balanced relationship between humans and wildlife. In his whitepaper5 Inter Species Money, Jonathan Ledgard proposes communities built around tending to the riches of the natural world - in effect, generating jobs, civic bonds and income from conserving and nurturing our natural capital. I don’t know exactly what that looks like, but the idea of a city that embraces it sounds pretty good to me.

Now, I accept that this vision is both thinly-researched and absurdly utopian - particularly when right now there isn’t adequate space for the human inhabitants of most cities, and in an era where a pandemic was likely created by a disease jumping from an animal to a human in a densely-crowded urban environment. Thinking about humans co-existing with nature creates issues of disease ecology and the sorts of germs that might evolve from this scenario that we need to consider.

But when I imagine designing our future city for its inhabitants, one way to approach it might be to stop just thinking about the human ones and consider all the species that might thrive in a city.

The rewilded city might not be carefully planned, easily contained, or quick to achieve. It also feels like it would never be ugly, destructive, or boring.

I know where I would rather live. What about you?

Thanks for reading. Part 2 of this will be a fictional exploration of what a wild London might look like.

William Macaskill - “What We Owe The Future: A Million-Year View”

The People and Nature Survey for England: Children’s Survey, October 2021

The Good Life 2030 - UK Citizen Research, 2021

The Economist, Lexington, “New York’s waters are being reborn”, Sept 1 2022

Jonathan Ledgard, Inter Species Money, 2021

This is so great!!!! I love your thoughts on the wild city! Can't wait to share this with my subscribers (and to read the fiction version!)