It is one of the greatest tragedies of human civilisation that Shakespeare never went into space

In the life span of the universe, the three hundred and fifty years separating Elizabethan England and the first Apollo mission in 1961 are just the blink of an eye, and yet they represent one of the greatest near misses in the history of the human race. We can torture ourselves trying to imagine what the greatest writer humanity has ever produced might have made of the experience of being shot into the heavens atop a giant firework, but it seems unlikely that it would have been dull.

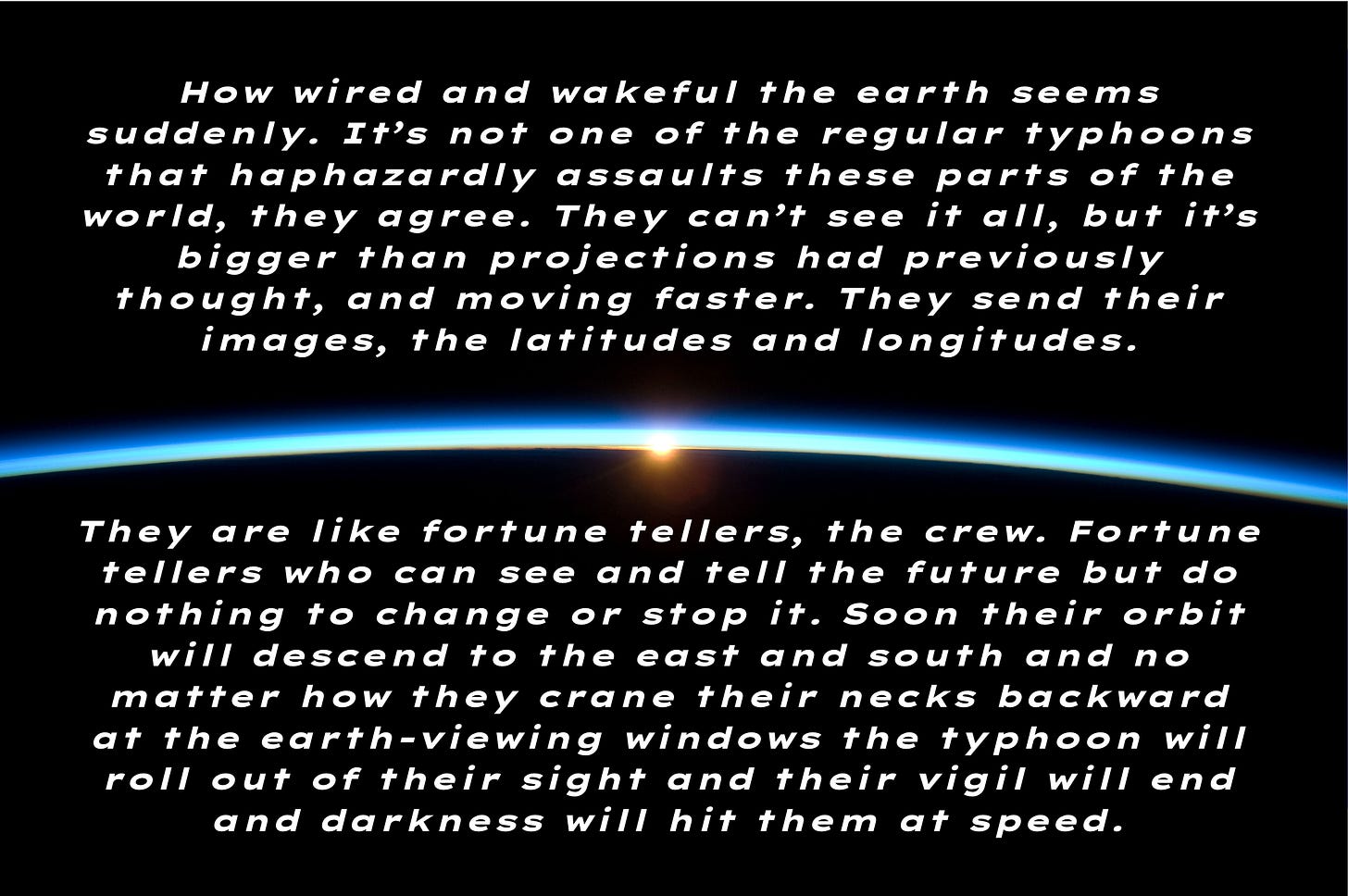

Even if we’ll never know what the results might have been had The Bard gone ballistic, those seeking a glimpse of what happens when literature takes space exploration seriously should pick up last year’s Booker Prize winner, Samantha Harvey’s Orbital.

Almost entirely plotless and written in prose that’s purple to the point of ponderousness1, Orbital’s Booker Prize win still represents an interesting shift - where one of literature’s most prestigious prizes has gone to a novel tackling territory that was once the preserve of science fiction. This simultaneously slight and vast book bridges the gap between high lyricism and the high frontier, and whilst it’s hard to say whether it’s a signal of a coming convergence of art and science, or a symptom of one already happening, it arrives at an interesting time.

With SpaceX catching starships with chopsticks, Blue Origin reaching orbit, The Artemis Missions returning to space in 2025, and even Toyota and Turkey pledging to get into space, the stars, once again, are where the action is. We have returned to an era where the launching of rockets is not only a spectacle of the technological sublime, but also a form of public entertainment.

This is good news for anyone who cares about science, imagination or human progress. Space exploration is the ultimate proving ground for rigorous imagination - a collective endeavour that demands a level of vision and creativity that would be considered insane if it wasn't backed up with billions of dollars and hard-nosed applied scientific thinking.

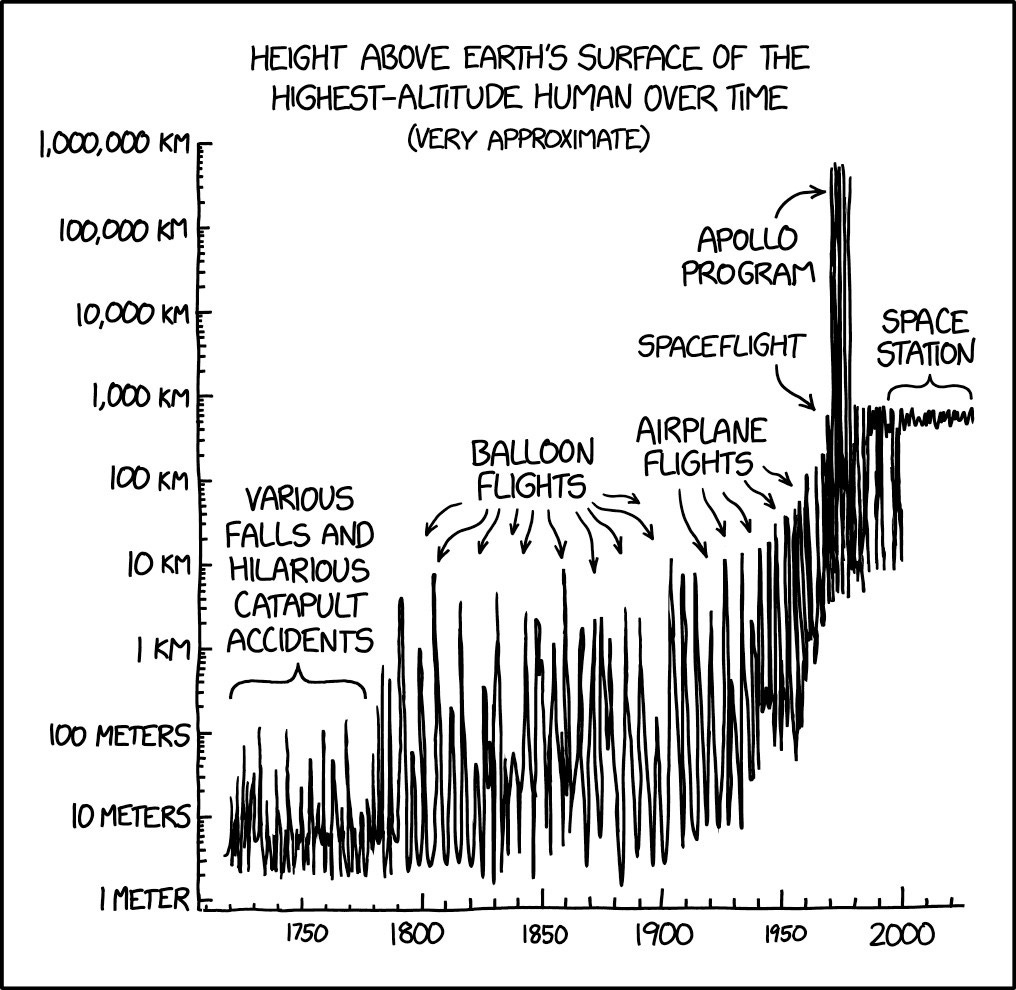

In some ways, the curious thing is not that space exploration is once again taking hold of the public imagination, but that we ever slowed down exploring it once we started.

The Apollo Programme, kicked off by one of the finest speeches ever written, and carried through by a mix of political will, organisational acumen and scientific genius, is still the echt-example of humanity’s ability to do big and difficult things.

When President John F Kennedy declared in May 1961 that “this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon,” no-one knew how to do it. Rockets, launchpads, space suits, hardware, software, zero-gravity food - they didn’t exist, and there were no experts in these domains - Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber, Boom - Bubbles & The End of Stagnation

It was an impossible goal with a ludicrous deadline: it’s not entirely surprising that when we look back at this era we feel nostalgia for the raw optimism and chutzpah that it takes to even suggest such a thing.

Amidst the maelstrom of collapsing climate systems, renewed great power competition and another Trump term, it’s easy to long for the ‘simpler times’, but there was nothing simple or easy about the intelligence on display when humans tackled these sort of problems. Space was the canvas and crucible for a highly technical form of imagination that still feels unparalleled in any other field of human achievement, and cultural objects from the first space age can feel like artefacts from not just another era but a different universe. For example, this.

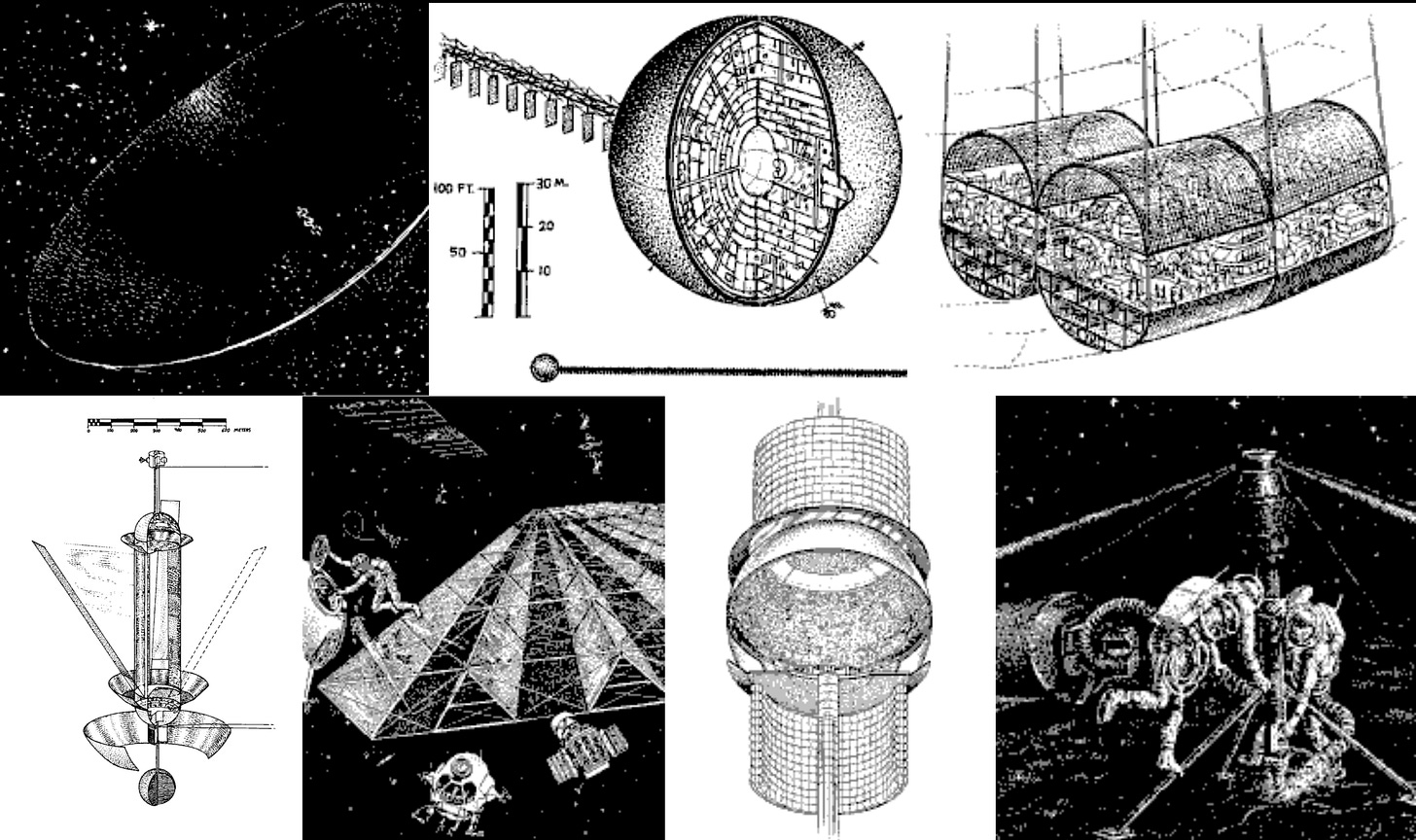

Gerard O’Neill’s The High Frontier was written in 1977, and lays out a coherent vision for how humans might live and prosper in space, complete with technical drawings and specifications for how space farms will work, the best way to position giant floating mirrors to harvest energy from the sun that we can beam down to earth instead of burning fossil fuel, and speculations about how people living in space will enjoy the pleasures of zero-gravity sex.

This isn’t just pie in the sky: O’Neill considered everything from the ‘ignition number’ of humans needed in space before we can start making things out there without extracting anything from Earth; the relative costs of moving mass for heavy industry into lunar orbit; and how floating agricultural farms might be modelled on The Crystal Palace of the Victorian Great Exhibition. As you read it, you become drunk on the sheer coherence and depth with which he envisioned humans living in space, and the casual way in which he made the impossible feel not only simple but inevitable.

A certain poignant feeling strikes when you realise that O’Neill believed much of the world he sketched out in the book would come to pass by 1990. Even if his timings were out, his vision and technical imagination are still highly influential: Gerard O’Neill was also college professor to one Jeff Bezos. Much of what is laid out in the High Frontier has influenced Bezos’ Blue Origin and its approach to how we might live in space - but the shift from NASA visionary to billionaire hobbyist may explain why not everyone is as excited this time around.

The Height of Human Ambition or Playground for Billionaires?

Cynics might argue that this time around the new space race is little more than a dick-measuring contest between billionaires, and all the rocket porn and shots of gleaming ballistic phalluses don’t help.

(This strain of criticism will persist until some female billionaire gets in on the race with an aerodynamic spacecraft designed in the shape of a vulva).

It’s hard to muster the same awe for the new space boom when one of those leading it is a prick of cosmic proportions. I am both impressed by Elon Musk’s achievements with SpaceX and appalled by almost everything else he does: I wish him the very best on his quest to get to Mars, and would like him to leave for The Red Planet immediately and stay there away from earthly politics and working internet.

Consider that, once upon a time, this was The Right Stuff that it took to be an astronaut.

‘The world was divided into those who had it and those who did not. This quality, this it, was never named, however, nor was it talked about in any way. As to just what this ineffable quality was…..well, it obviously involved bravery. But it was not bravery in the simple sense of being willing to risk your life. The idea seemed to be that any fool could do that, if that was all that was required, just as any fool could throw away his life in the process. No, the idea here (in the all-enclosing fraternity) seemed to be that a man should have the ability to up in a hurtling piece of machinery and put his hide on the line and then have the moxie, the reflexes, the experience, the coolness, to pull it back in the last yawning moment - and then to go up again the next day, and the next day, and every next day, even if the series should prove infinite - and, ultimately, in its best expression, do so in a cause that means something to thousands, to a people, a nation, to humanity, to God.’ - Tom Wolfe, The Right Stuff

Yes, the downside of the privatisation of space travel is it becoming an elite hobby for billionaires rather than only the preserve of a few brave souls at the frontier of human experience. But to pour scorn on returning to space merely because we resent the very rich people spearheading it overlooks the massive benefits that come with it nevertheless.

The Overview Effect

One criticism often levelled at the new space race is that it’s an exit strategy for people who have given up trying to fix earth and its climate. But the binary that we must either devote our energies to leaving the earth or saving it has always been a false one, not least because of The Overview Effect.

One of the primary effects of entering the celestial realm, as explored in both Harvey’s Orbital and in Stewart Brand's original campaign to have the Whole Earth photos from space released, is that it forces upon us a Godlike view of our planet and its fragility amidst the emptiness of space.

The release of the Earthrise photo gave birth to the environmental movement, and it helps us see that we are, to quote W.H. Auden, 'Children of a modest star'. We need it now - in an era of fraying political relationships and increasing nationalism - more than ever.

One of the more provocative insights from The High Frontier is that O’Neill believed it would be easier to master the laws of physics leave earth than it would to slow the runaway train of resource extraction and environmental damage that is modern capitalism, or change the deep-seated irrationality of human behaviour en masse. For him, the only way for the human race to keep growing whilst preserving the earth was to give us a much broader canvas to work on: whether you believe him to be wrong or not, as a bet it seems like a pretty sensible use of humanity’s resources, or at least just a worthwhile an insurance policy.

I have little desire to treat earth like some ruined Eden that we must cast ourselves out of to save it, nor do I wish for the only legacy we leave for our grandchildren be for them to have no choice but to abandon our planet. But the fact that our world is fragile and our future is uncertain is not a good reason to cease going into space in search of scientific knowledge, and it never has been.

‘Human life has always been lived on the edge of a precipice. Human culture has always had to exist under the shadow of something infinitely more important than itself. If men had postponed the search for knowledge and beauty until they were secure, the search would never have begun’ - C.S. Lewis, Learning During Wartime

The Overflow Effect

Space exploration comes with not just an overview effect, but an overflow effect too. In exploring space, we trade ignorance for discovery in concrete form, and not only from the experiments that are carried out by the crew of any vessel out there. It is no stretch of reality to imagine each space mission as a trade ship that we send off into foreign lands, and which returns bearing a rich bounty of new knowledge and innovation.

The list of inventions created and scaled due to space exploration is long and exhaustive, but it includes baby formula, memory foam, camera phones, CAT scans, LEDs, artificial limbs, foil blankets, portable vacuum cleaners, home insulation and freeze dried food.

In an age where ‘innovation’ seems often to suggest increasingly incremental inventions wrapped in the promise of the future but which deliver few genuine benefits, space exploration promises a return to hard atom-based progress. And the overflow effect of a new space boom will not stop at the inventions and scientific progress. The stars aren’t only a proving ground for science, they are a canvas for art.

Space is the natural place where the poetic meets the scientific, and where the heights of human wonder and invention meet engineering prowess and hard science. Much has been made of the need to create consilience between science and the humanities, STEM and art - but if we’re seeking place where the two cultures might meet, we do not need to look very far, but merely to look up. In the mystery and poetry of space exploration, the vast dark canvas of the stars and the hostile vacuum of the infinity beyond our world, there is a well of inspiration from which we can draw forever.

AI’s effects on art and creativity might be a bigger topic of public debate, but I am just as excited by the vast new range of artistic expression that might be within grasp once travelling to space becomes accessible to greater numbers of people.

No, unless someone invents time travel, we will never get to read what Shakespeare might have written if he’d gone into space. But if even stranded on earth and slaves to gravity, our capacity for wonder at the beauty of the night sky can produce Starry Night, what happens when the next Van Gogh gets to go to space?

The powerfully strange and deeply aesthetic experience of galactic travel is likely to trigger a similar response in any artistically-minded human being lucky enough to go. There is already a rich lineage of great writers of the sea and sky: if aviation and ocean navigation have already triggered near-religious levels of inspiration, when will we get our Joseph Conrad, our Herman Melville, our Antoine De Saint Exupery of the stars?

In The High Frontier’s meticulously researched scientific imaginary and Orbital’s flights of pure verbal invention, we get one half each of the kind of deep technical knowledge and literary metaphysics that were combined in Moby Dick. The hope is that perhaps space becomes a vast page on which art that has room for both emerges.

Not least because space is fundamentally unconquerable, ungraspable, unknowable. We might explore it and understand it better, but we will never get to the end or even the edge of it: there will always be parts of it that like beyond our reach - and mystery remains the fire of the human imagination.

A world where we once again lift our gazes up to the heavens, rather than down at our smartphones, is one that I would rather live in. If you know anyone with a spare seat in a rocket hitting escape velocity any time soon, count me in.

For the record, I am glad Orbital exists but believe that Percival Everett’s James is a vastly superior novel that should have won The Booker.