It all feels wrong from the start.

You take the pitch for a new project via a third-party intermediary who won’t say who the client is or what they want, and you know then you should walk away. All they’ll say is that they’re a department of the government with a highly unusual set of goals who are prepared to do almost anything to achieve them.

The upside is that they have good money to spend. The only downside? If it works, you will never be able to talk to anyone about what you did, and just to attend the meeting you’re made to sign a scary-looking NDA confirming the client’s right to deny ever having spoken to you if the project ever goes leaks to the public.

The meeting, if that is what it might be called, goes down in a nondescript building on the South Bank a stone’s throw from MI6. You are summoned into a poorly-lit basement room filled with smoke, and the client proceeds to give you the briefing.

They persist in referring not to the ‘target audience’ like most marketers do, but merely the target. It is an ‘influence operation’, and what you are being asked to do seems, if not outright illegal, then at least ethically murky. All they ask for is talent, and discretion.

You leave confused about what just happened, and with only one big question:

Is this advertising, or is it a Psy-Op?

Let us halt the fictional thought experiment for a moment. The scenario I’ve just walked through might seem implausible, but we live in an era where everywhere you look a battle for the human mind is happening. It’s an oft-repeated cliché that the internet of 2023 feels like a battleground: every conversation and gesture online seems like a shot fired in some larger persuasive conflict, with each side pushing the red nuclear button at the earliest possible moment. Many online arguments are now stalked by accusations about one side or the other carrying out Psy-Ops - shorthand for Psychological Operations.

The internet is no longer a metaphorical battleground, but also a literal one. The ultimate prize? The human mind. As the author of ‘Cognitive Warfare’ put it:

“The modern concept of warfare is not about weapons but about influence”1

Over the Covid-19 Pandemic, misinformation about vaccines turned out to be almost as contagious as the virus itself, and deadly for some of those who chose to believe it.

In the early days of the Russian Invasion, the CIA made the unprecedented move of declassifying live and sensitive intelligence about Russian military actions to ‘pre-inoculate’ the global public against the inevitable misinformation about what was really happening on the ground. This was complimented by online sleuths and armchair intelligence operators tracking Russian tank and troop movements via videos on Tiktok and other available dash-cam video footage.

Open Source Intelligence movements like Belingcat and Forensic Architecture sift through the vast amounts of available satellite and social media data to investigate everything from the downing of the Malaysian Airlines flight to human rights abuses and the Beirut Port Explosion.

In a recent interview the head of the UK’s National Cyber Force claimed that they aimed for ‘cognitive effect’, and NCF state that “the intent is sometimes that adversaries do not realise that the effects they are experiencing are the result of a cyber operation2”.

More recently, in 2022 TikTok influencer Hailey Lujan started an online uproar when she pivoted from standard influencer behaviour into becoming a nubile unofficial recruiting sergeant for the American military, complete with phallic gun-toting, fundraising for veterans, and all the inevitable camouflage and merch you could shake an automatic weapon at3. She proudly declared herself a Psy-Op Specialist.

‘Mindwar’ or ‘cognitive conflict’ - the battle fought for the hearts and minds of humans - is serious business. A 1980 military paper argued that the reason America lost The Vietnam War was because it was out-Psy-Oped by a more agile and creative enemy, concluding: “better hardware is nice, but by itself it will change nothing if we do not win the war for the mind4”. If this was the case in 1980, then the internet has given it a steroid injection.

How else do you explain the recent upsurge in American political hostility to TikTok? If a platform commands the majority of many internet users’ attention, what would happen if someone decided to use it to push an agenda more sinister than popularising the Negroni Sbagliato? In a connected world, media and creativity are nuclear and biological weapons, paving the way for what American artist Trevor Paglen has called “Psy-Op Capitalism”5. And if you work in the creative industries, you might not be an innocent bystander in this particular conflict.

The thin line between persuasion & manipulation

Given that the flaw of many people in creative communications is an almost comic level of self-advertisement, it might seem ridiculous to suggest any kinship with the world of secrets and tradecraft.

But if advertising can influence everything from people’s choice of car and supermarket right down to public health messaging about smoking cessation and skin cancer prevention, it can also be bent towards goals that are less commercial and more military or psychological. The harder you squint, the more the line between commercial creativity and psy-ops starts to look disturbingly thin.

Most of the language of communications strategy is explicitly lifted from military strategy. The UK army recently announced the creation of a specialist 77th Brigade, created for ‘Information Operations’, but advertising and creative persuasion has been a weapon of choice for recruitment into the military and espionage communities, as shown by the fact that several agencies in London continue to do recruitment advertising for the Army, Navy and Airforce, as well as some rather discrete work to drive applicants for MI6.

Back in 2019, the American Armed Forces attempted to solve its recruitment issues using Call of Duty and E-Sports as a means of connecting with future soldiers, until the partnership collapsed in a cloud of acrimony.

As a less sinister example: one of my favourite case studies of the last decade or so is that of Lowe Colombia finding a creative (and non-lethal) way to get FARC guerrillas to demilitarise and leave the jungle.

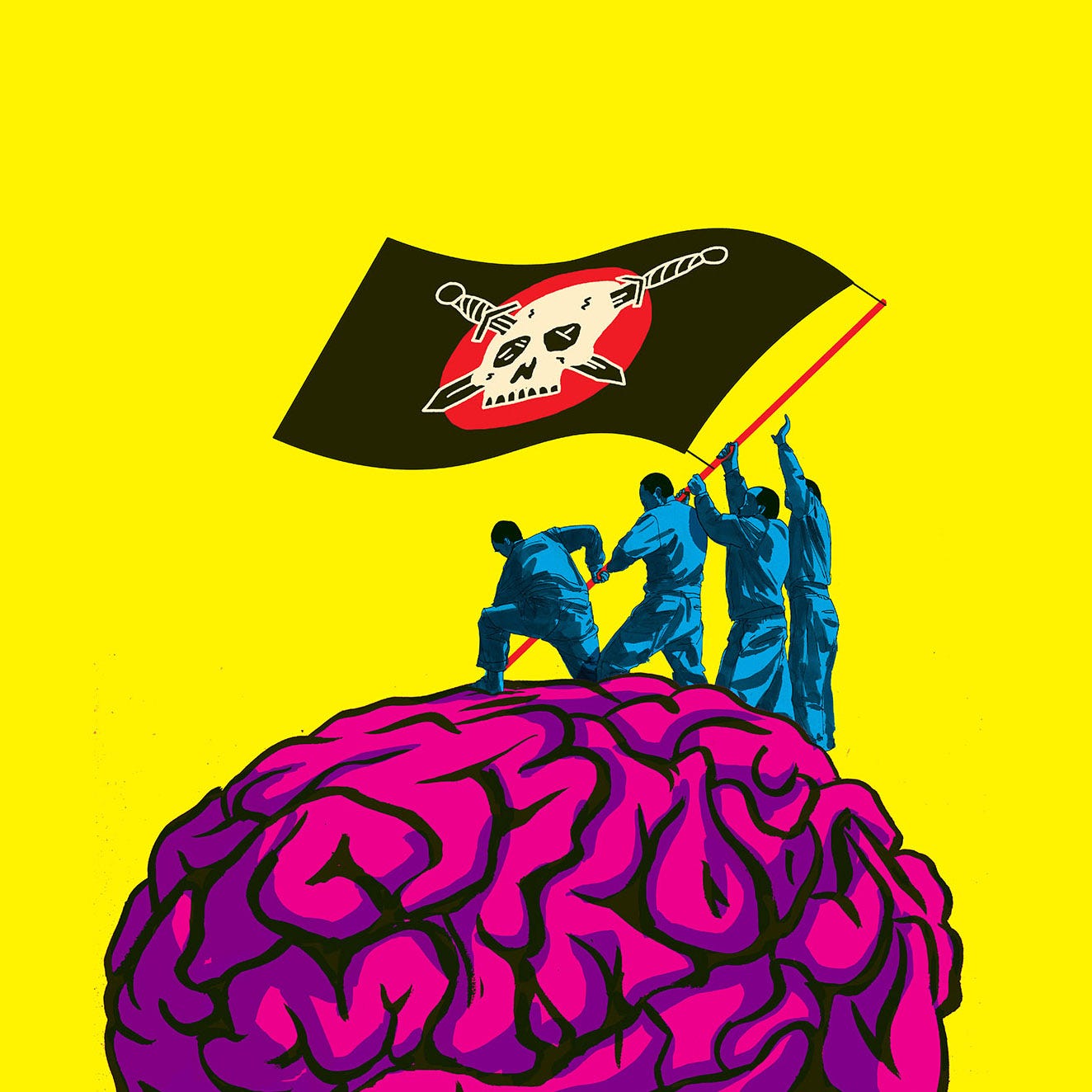

It’s worth considering the disturbing idea that working in communications means you aren’t the commercial arm of the arts and culture industries or the more glamorous wing of the consulting machine, but the creative tentacle of the military-industrial complex. Creativity is a weapon we all wield every single day, and that makes us the shock troops of Psy-Ops. So go ahead, pick your preferred unit badge.

Weaponised Creativity

Even if the usage of creative persuasion for military and political recruitment triggers your ethical gag reflex, it’s fascinating, and it is merely the outward-facing expression of a form of weaponised creativity that’s been going on for a very long time.

I’ve written before about films like Top Gun and Captain Marvel being explicit American soft power propaganda, but there is a long and remarkable history of state and non-state actors using culture, creativity and media for political or ideological ends.

Over the course of WW2, the US had a division referred to as the Ghost Army counting artists like Ellsworth Kelly, Bill Blass and various others, who used trickery, deception and creativity to alter the enemy’s perception of troop numbers, weaponry and military manoeuvres.

In the spectacular ‘Active Measures’, Thomas Rid details the long history of countries and ideological blocs using creativity, culture and misinformation as a weapon against one another, and often their own populations too.

The State Department and CIA pulled strings to send jazz musicians Nina Simone and Louis Armstrong on world tours to countries they feared would turn to Communism, and they also mass-printed Russian-language copies of Dr Zhivago and smuggled them into the Soviet Union to stir up criticism of the Bolsheviks. They were not afraid to use any means necessary: one side-effect of the Cold War was Schlagzeug, 1950s Germany’s most popular jazz magazine, and in one case US-affiliated West German organisations also organised “a direct attack on advocates of Moscow Communism through the vehicle of astrological analysis and prophecy.”

They even created their own dating service, and whilst it’s easy to admire or laugh at of it, this shit is still happening.

Between 2011-2017, Psy-Ops operations against Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army used the voices of soldiers’ mothers begging them to come home6.

More recently, the CIA briefed a toy designer from Hasbro responsible for GI Joe to prototype frightening action figures of a devilish-looking Osama Bin Laden in an effort to make Pakistani children afraid of him.

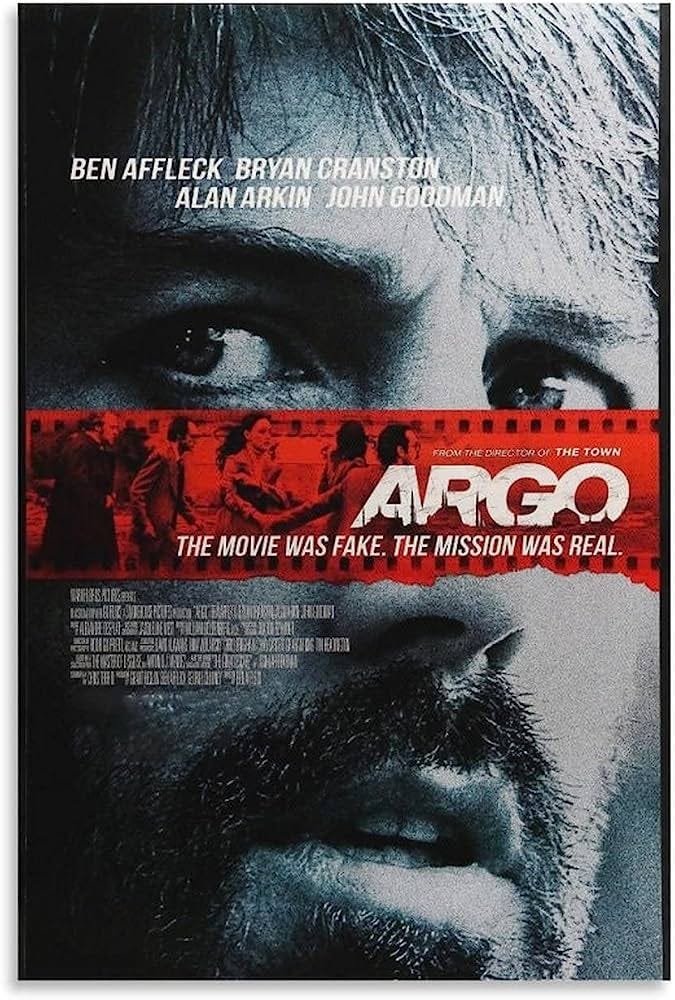

The fact that the story behind Argo itself is in the public domain as an Oscar-winning movie, is itself not an entirely innocent one: it was declassified by a CIA director to get a positive story about the agency out into the public domain given that most of the time people only hear about them when something goes wrong.

Lest we think that this is a uniquely Western or American phenomenon, Chinese movie Wolf Warrior has become a shorthand for their current brand of aggressive foreign politics, and the Russians can lay fairly conclusive claim to having invented the art form of misinformation in the first place.

Perhaps the peak and nadir of this was the KGB’s creation of the myth that America created AIDs as a weapon. The KGB also fabricated foul racist pamphlets illustrating the truth about America’s treatment of its Black citizens to drive a wedge between the USA and African nations they were worried would turn towards the West.

Psy-Ops were hard to trace and it’s harder still to pin down the exact impact of their rippling cultural and psychological effects - to paraphrase a popular adage about marketing impact, ‘I know half of my information warfare is wasted, I just don’t know which half.’ Most recently, journalist Patrick Radden Keefe spent a year of his life trying to find out if The Scorpions’ ‘Winds of Change’, the hair metal power ballad that soundtracked the fall of the Berlin Wall and eventual collapse of The Soviet Union, was in fact a CIA Psy-Op7.

(If this is true and anyone from the CIA is reading this, get in touch - you’ve got an absolute solid gold IPA Effectiveness Paper as well as a good pitch for an Ivor Novello in there).

Studying all of this is revealing even if much of it involved appalling goals achieved by devilishly brilliant and utterly odious methods. What isn’t in question, amongst this murky history of lies and deception? That creativity is an extremely powerful tool, and that those who wield it should do so carefully. Don’t take my word for it, ask the CIA, the KGB, MI6, the GRU……

So if the veil is lifted and we are no longer innocent of the power in what creativity can be used for, then what are we to make of our role in all of this?

The Dangers of Creative Weaponry

There aren’t a lot of easy answers to where communications professionals sit on this line.

Perhaps the biggest dividing factor is about scale: advertising and brand building is a sociological activity, intended to build shared meaning and common reference points about what a company or product is. Psy-Ops are often individualised and intended not to unite but to divide, to exploit existing ideological and sociological fissures and breakdowns and widen them. They divide and conquer via creative means, and no brand-builder wants to split their audience. But other similarities persist. As Thomas Rid8 states about the best kind of disinformation:

“Even if no forgery was produced and no content altered, larger truths were often flanked by little lies.”

The uncomfortable conclusion to all of this is the thought that the shadow side of the ability to empathise we all so highly prize is the ability to manipulate. There is a very fine line between the truth creatively expressed and underhand dirty tricks exploiting our innermost desires and fears. Most pertinently: the better a society is at misinformation and psy-ops, the worse for their democracy. The impacts of mobilising misinformation as weaponry are corrosive to an open society and democratic process, and the seepage from the military sphere into every corner of debate and online behaviour is one to lament. This is the famous Foucalt’s Boomerang in action, where the tools of warfare and repression deployed by imperial powers against their enemies inevitably get turned inwards on their own populations too.

Given Psy-Ops are often most powerful when conducted in highly targeted and one-to-one ways, it’s a reminder for anyone working with mass media that audiences and citizens wield a great deal of power and influence. Psy-Ops players of previous eras have created political movements using little more than forged letters and magazines: the modern audience has a lot more production and media weaponry at their disposal. Mass media doesn’t entail a monopoly on impact nor cognitive effect.

In an era where the free availability of AI means that the mass production of misinformation and psy-ops content can occur at unconstrained scale and levels of personalisation, this could all get worse before it gets better.

You have only to look at the emotional fallout earlier this year when AI companion chatbot Replika suddenly stopped responding to the sexual advances of many of the people who used it. Now imagine that chatbot was controlled by a hostile non-state actor, and could use its emotional grip on lonely internet users to turn them into assets in sabotage, violence and activism. If you aren’t a bit frightened by this, you should be.

The New Ethical Code of Creativity

So what to do other than throw up our hands and be caught in the crossfire? If the secret and often justified concern of many working in commercial creativity is that much of what we do is both shit and ineffectual, then the historical precedents for just what creativity, in its broadest form, is capable of achieving should be both inspiring and disturbing.

When you see the ends to which benign and malign actors have deployed communications in the past and the cultural and political impact they’ve achieved, it makes you realise the utter ambition poverty of creative agencies pumping out scam work aimed at no-one but Cannes Award juries. What we do is extremely powerful if used in the right way.

But most of all, it should be a reminder that we need to think very, very carefully about what we do, where creativity can elide into manipulation, and the second and third-order consequences of using the wrong methods.

The best code for us all in these murky times is one from the late, great Dan Wieden:

“Advertising is a weapon. Be careful where you point it.”

François De Cluzel - Cognitive Warfare, 2020

https://www.economist.com/britain/2023/04/04/cyberwarfare-is-all-in-the-mind-says-britain

https://www.punctr.art/because-physical-wounds-heal/

Paul E. Valley - From Psy-Op to Mindwar: The Psychology of Victory, 1980

pacegallery.com/journal/trevor-paglens-abridged-guide-psyops/

Source: https://paglen.studio/psyops/

https://crooked.com/podcast-series/wind-of-change/

Thomas Rid - Active Measures: The Secret History of Disinformation & Political Warfare

Brilliant and completely true, thanks for writing this. State actors arent the only ones doing this — the problem of art being used to manipulate is pervasive throughout modern culture, but it stretches back into previous eras as well (The Dutch Old Masters, with their perfectly-curated interiors, were not so different from the current instagram-influencer psyop accounts and their immaculately-presented public lives). I'm very interested in the religious angle as well. We all know Christian films are terrible, and that's no doubt in part because Christians are trying to ram a message into the minds of the films' viewers. But is that any different from the latest Disney cartoon with its inevitable "follow your heart" message? Your examples of Armstrong and Simone being sent on tour as "ambassadors of goodwill" was particularly spot-on. Thanks again.