New Year & The Multitudes Within

An open letter to anyone who's already abandoned their New Year's Resolutions

By today, many of us have already given up on the people we might have been.

There isn’t widespread agreement on exactly when Quitter’s Day is, but somewhere between the 12th and the 19th of January most people’s New Year’s Resolutions hit the wall. The willpower we thought we had encounters its reality collision moment, and we go back to being the person we once were.

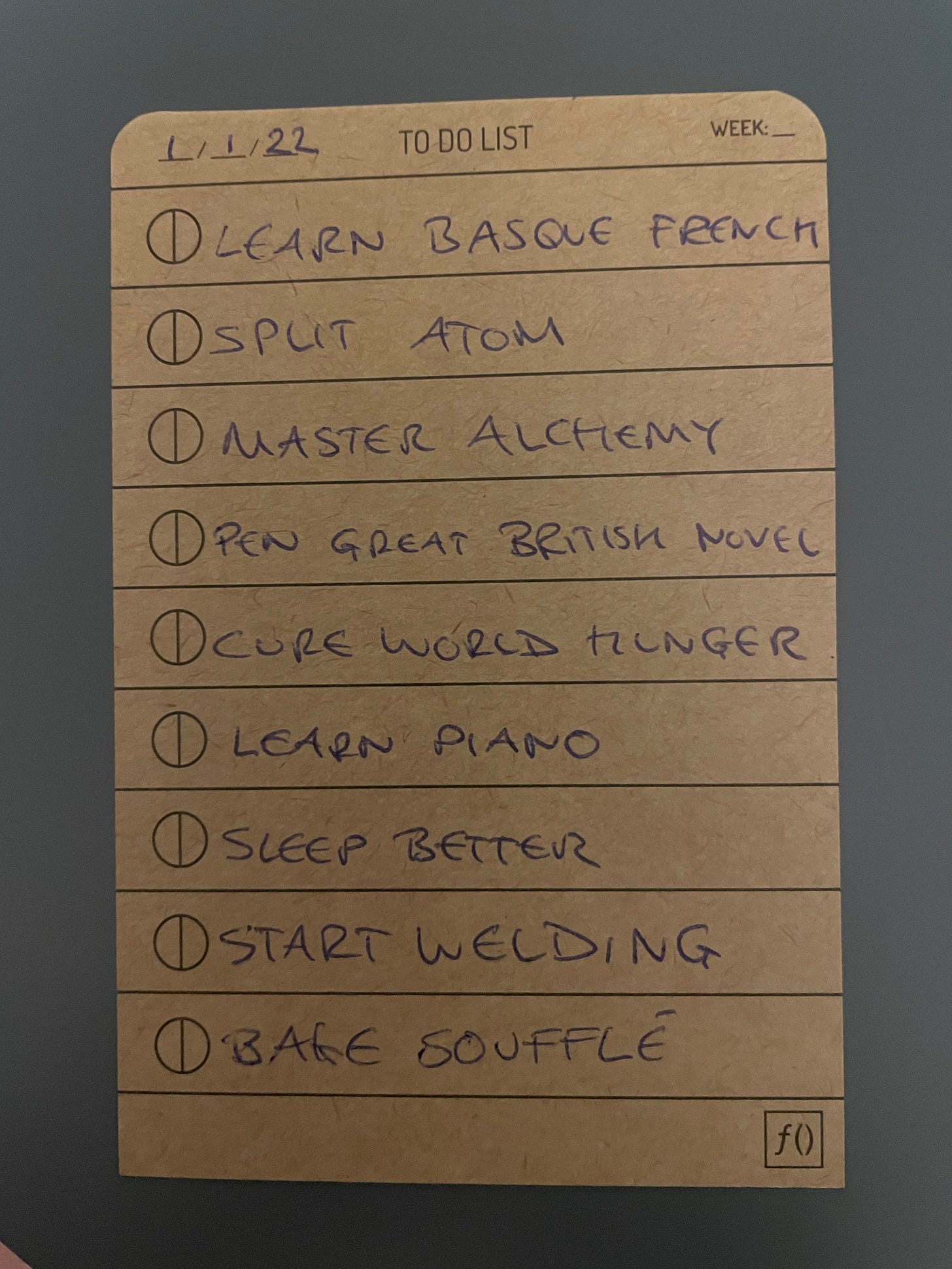

I, like almost everyone else, am prone to using those limbo days in between Christmas and New Year to make insane lists of resolutions and behaviours - almost all of which come to naught. On December 26th I, like Walt Whitman, contain multitudes who will finally be unleashed on the world. By January 15th, I have encountered my own limitations and gone back to being the one person I’ve always been. By mid-January it’s hard not to find yourself staring at the funeral pyre of broken promises to a future self, depressed by all the failed resolutions and deflated ideas. Dreaming and failing seem somehow worse than having not made any resolutions at all.

But this year is different. Before Christmas I watched the luminous Past Lives, and it served as a bracingly beautiful warning about this kind of magical thinking. It offers as its premise a simple question: if you fell in love with and spent your life with someone else other than your current partner, who might you have become? What if you got a second chance to answer that question - what would you do? Who would you choose to be with, and to be?

It made the usual New Year’s act of trying to be too many people for one life to hold feel naive, and it also seems to be an elegant artistic counter-response to something of a trend in cinema at the moment. Looking across Everything Everywhere All At Once, Barbie, and The Marvel Comics Multiverse, we seem to be at one of those strange confluences in pop-culture that is obsessed with the roads not taken, the lives that we might have lived, and the many selves that live inside all of us but are defeated by circumstance.

Multiplicity is having a moment

We can hazard a few guesses at why: on social media, it’s never been easier to cosplay or LARP as someone else. We’re living longer, and there’s fewer clear life paths, and less hard boundaries on a lot of the traditional transitional markers from one to the other. We’re starting to understand that people occupy many roles in their lives and that those might not be as clear-cut and linked to age as they once were.

It’s not a coincidence that many of the movies exploring multiplicity have women as their protagonists: how many selves have women had to sacrifice to societies that don't want or allow them to live freely? How can you not think about who else you might have been when you’re going through the huge identity rupture caused by motherhood?

It’s perhaps too much to hope for that a cultural moment dedicated to the unlived lives of women might be a trigger for a greater number of women’s dreams being realised. But we can hope. Whatever the explanation, it’s certainly no bad thing. Who wants to fit neatly into just one box?

Great movie fodder, terrible life philosophy

But whilst exploring multiplicity makes for great cinema, as a philosophy for living it’s dangerous. Watch too many of these sort of films and the act of breaking a New Year’s Resolution starts to become a special sort of personal betrayal. But trying to live a good life has always involved the entangled issues of compression, compromise and commitment familiar to anyone in mid-life: how much do you try to fit into your days, when do you trade off, where do you commit? These kind of questions about how to live have persisted for a long time, but perhaps more than before we are being told that we can have it all. The problem with the cultural idea that anyone can be everyone whenever they want is that it makes choosing to be one particular someone feel like a form of punishment.

Finitude is part of what makes us human, and the idea that there’s no limit on how many people we can be is always going to bump up against the inconvenient constraint of death. Despite the developments

has been exploring in his pamphlet on immortality, it’s going to remain that way for a bit.Having to choose how to live and which path to take is part of the agony and ecstasy of being human, and one of the things that separates us from both the animals and the gods.

“Neither the beast nor the puppet is cursed with self-reflective thought. That, as Kleist sees it, is why they are free.”- John Gray, The Soul of the Marionette

Walt Whitman might have famously summoned all the swagger and unswerving optimism of a young America when he said, "I contain multitudes”, but if you want to understand what actually happens when you try to live too many lives, and when your unlived lives are more real than you are, read some Fernando Pessoa.

Portugal’s national literary icon lived a quiet and shuffling life, faced with indifference to his work for much of his career bar publishing one slim volume of poetry. But after he died, a sealed trunk containing his work was opened, and revealed the truth: Pessoa had spent his life creating a series of heteronyms - an accountant called Bernado Soares, Alberto Caeiro, Ricardo Reis, Álvaro de Campos - with their own voices, backstories, points of view and literary output. These were not thin noms de plumes: one was an accountant, the other a naval engineer, another a doctor. It seemed impossible that any one person could sustain such a vast and plural array of different selves.

After his series of literary alter egos were publicised, Pessoa became an icon of modernism, a figure of national literary importance, and a totemic global figure of literature. Pessoa created and sustained a phenomenally vivid array of literary characters who were, in his own mind, far more real than he was - an artistic eulogy for the unlived selves that live within all of us. This was a man who would have had to write a different list of New Year’s Resolutions for each of his alter-egos, and trying to fulfil them would have driven him mad. He gave up his own life to sustain a series of dreams in literary form, and can be viewed as the epitomy of what happens if you give the multitudes within all the space they can take.

“In the vast colony of our being there are many species of people who think and feel in different ways.” - Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet

His grand theme was the torture of believing that there is far more in you than will ever see the light of day, and being unwilling or unable to cope. In response to Whitman's "I contain multitudes", Pessoa's "Quantos Eu Sou?" (How many am I?) seemed to admit the agony and the ecstasy of multiplicity – at least to a modern reader, it sounds more like "how many might I be, or could I have been, if I had the time?".

He knew and experienced the reality of containing multitudes: they had to be hosted like parasites. Each needed energy, vitality and time to sustain their existence, which was leeched from the soul of whoever gave birth to them - and no-one could be the person they feasted off without living a sort of half-life, with its attendant problems of fracture and fragmentation. The irony, of course, is that Pessoa dedicated his existence, in a maniacally committed way, to writing about failing to achieve anything, and as a result became a legend.

But there’s a great deal of warning contained in his life story. I accept, with regret, that even if I write down all of the many selves I wish I could be and lock them in a trunk, no-one is going to disinter them after my death and use my broken New Year’s Resolutions to make me into an international literary icon. Spend too long starting unfinished chapters of the story of your life, and eventually the result will be an incoherent mess that never really begins:

“A tragedy booed off stage by the gods, never getting beyond the first act” - Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet

If we take the modern ideal of the many selves too seriously, commitment to anything becomes a form of punishment, and every meaningful choice we make is a sort of massacre of all the people we might have been. But that doesn’t account for the simple truth that time, at least as we humans experience it, only travels in one direction. Whenever you do anything, an infinite numbers of doors slam closed forever - that’s how you know that your life is real, and not just a series of dreams made in December and shattered by mid-January.

Forget All The Roads Not Taken

I don’t mean to suggest that everyone doesn't contain within them the capacity for plurality or self-renewal. I am, at heart, someone whose idea of a good life is one with a few different chapters and episodes.

As Zadie Smith says,"if novelists know anything it's that individual citizens are internally plural: they have within them the full range of behavioural possibilities. They are like complex musical scores from which certain melodies can be teased out and others ignored or suppressed, depending, at least in part, on who is doing the conducting"1. But even if we all have within us the capacity for many movements, moods and tempos, eventually we must decide which song we want to be.

In an era where time and attention are commodities, there’s always another visible option or path we might have taken, and we can spend our lives dwelling on all the roads not taken. it's easy to endlessly mourn our unlived lives: to blame our parents for closing off paths prematurely, our friends for not encouraging us to follow them, our life partners for taking up time that we might have devoted elsewhere, or to project our unfulfilled dreams onto our children in the hope that they can live the ones that we did not. But it’s far more freeing to acknowledge that commitment is the coin the world demands of us in exchange for a good life.

If this piece/rant/eulogy resembles a sort of internal pep-talk in public, that is no accident - I fear myself a lover of many things and a master of none. The people I most admire are those who seem not to be plagued by the question of how to live and just get on with it. One of the many reasons that I found Past Lives so affecting is that it resists the familiar narrative turn where the character gets to replay a lost might-have-been - it’s far too mature a piece of cinema for that. Its final moments are so moving because they depict someone who knows that they must choose a life, the person they spend it with and whom that they will turn out to be, whilst acknowledging that it might have been different - and that the life they have sacrificed would have been, in its own unique way, beautiful too. The abandonment of all the other roads is what gives the one you’ve chosen its meaning.

We must dedicate ourselves to something and someone in order to live in the world, and spending our narrow span of time endlessly mourning all the people we might have been is an early death sentence for the person we are right now. A fully lived life is the prize, and commitment is the price.

So happy Quitter’s Day, and Happy New Year. May it be one with a very short list of resolutions to break, and a great deal of commitment.

Thank you for reading.

Zadie Smith, 'On Optimism and Despair', in Feel Free

The damned January frost is making it difficult to stick my flag in the ground but completely with you on this.