Any true fan will die, or kill, for their idol. Won’t they?

In Donald Glover’s latest show Swarm, fan love is deadly - it revolves around a thinly-disguised Beyonce fan murdering people who dare to profane her goddess.

It’s telling that America’s Most Talented Man has put his finger on the dark side of pop cultural idolatry - swipes at The Beyhive aside, fandom isn’t short of fans right now. Fans are where culture, art, the internet, culthood, religion, and cold hard cash meet.

Dedicated fans allow artists to go ‘direct-to-consumer’ and make money after 15 years of low-interest-rate cash and plentiful investment dollars let streaming monoliths and platforms choke competitors out of entertainment markets, and thus gradually dictate what artists get paid for what they do. Savvy artists who can engage, stoke and amplify the passion of their fans can also monetise it in a range of ways - be that merchandise, content, experiences or beyond. As any long-suffering football fan will tell you, the ardour of fandom is almost price-inelastic - you can keep upping the price of tickets, merch and associated services and true fans will often keep shelling out.

In marketing everyone is a fan of fandom

Fan communities are the test lab and creative studio for online culture. In the case of Taylor Swift fans taking on Ticketmaster or the activism of BTS fans, their passion for creators also can be mobilised to create political injustices or economic issues. Devoted fans bring a jolt of unpredictability to an algorithm-dominated online landscape, turning art into signals instead of noise through the sheer power of their love - they are the jury members of culture, swaying a logic-driven judge.

As I’ve pointed out elsewhere, the culture that we love is often a far more effective indicators of identity than many of the other datapoints we use to define people. The fire of real fandom burns so hot and deep that it can shape someone’s sense of who they are for the rest of their lives: people who discovered punk or hip-hop as teenagers are likely to have found it a foundational and formative force that still shapes their fashion leanings, brand preferences and even voting choices1. I recently attended the “Beyond the Streets” exhibition at Saatchi Gallery and was struck by how many great artists’ initial creative energy was expressed as fandom for musicians and bands that they loved.

For marketers, dealing with fans is liberating: it gives you a clear audience, shared lore and cultural references, and a crowd who will interact with what you create and signal boost it to make sure a wider audience overhears. It inverts the model of how a lot of marketing has worked - starting with someone’s love and building experiences, services and content to meet it rather than vice versa. If you’re interested in the best thinking in this field, look up Dr Marcus Collins, Dan Runcie, Zoe Scaman or Jordan Dinwiddie.

Fandom allows marketers to move beyond the chronic tone-deafness that haunt much of what we do. Brands often speak to their customers like morons: engaging with fans requires understanding of the deep context and emotional attachment of their relationship, and speaking directly to it. Smart mass market consumer brands are learning from all this. McDonalds have reinvigorated their business2 through high-profile meals machine-tooled for fans of icons Travis Scott, Saweetie, BTS, and J Balvin.

Fandom is artistically liberating

Having such dedicated audiences isn’t just good for marketers, it’s also artistic dynamite. We hear a lot the entreaty for artists to ‘never forget where they came from’, or the audiences that helped lift them to prominence - but a community might not only be hometown or early fans. Virgil Abloh had plentiful fans and co-creators in his artistic retinue, but he also had a very particular audience in mind for everything that he did.

Writers and artists who remain accountable to such audiences, real or imagined, have an internal compass and a sense of fidelity to the truth that makes for dynamite. There’s often a political bent to this, particularly for writers channelling the voices of the unheard or marginalised - it can mean writing on behalf of a group of people who might not even be listening. In the case of Min-Jin Lee writing about Korean migrants in Japan for Pachinko, women whom she has never met but respects:

“I wanted to write about the woman that I see on the subway or waiting for the bus in the winter wearing a threadbare coat, or the woman who works as a cashier at an H-Mart - I am interested in the physicality of women who live their daily struggles with integrity” - Min Jin Lee3

We’re used to thinking that certain art forms - live music, theatre, stand-up comedy - rely on the symbiotic relationship between performers and their live crowd. But all artists are in collaboration with their audience, and great creators need their portion of Ernst Gombrich’s “Beholder’s Share” for anything they make to feel truly alive. Great works of creativity endure not because of their completeness, but because of what they ask of their audience to put into them: Shakespeare is still for all time because his plays are contingent and include a lot of unusually opaque gaps in direction, action and stagecraft which directors and performers can fill with their own variations on the material4, breathing new life into them. As Oscar Wilde put it, “there is no such thing as Shakespeare’s Hamlet5”. The modern fan provides an evolved version of this.

It’s easy to get excited about the vogue-ish and internetty dimensions of this stuff, but it’s happening IRL too. Marc Quinn is about to take community contribution to its natural limit with his artwork Our Blood, which invites people to contemplate the similarities between two separate glass cubes full of human claret. The only difference? One contains blood drawn from refugees and the displaced, the other from non-refugees donors.

Even if they haven’t given blood, it’s an inarguable truth that modern fans play a more active and varied role in the creation of art than at any point in history. Modern artists are inviting the viewer in, masterfully orchestrating their audiences, and in certain places are establishing their own agencies and incubators to in-house the process of creating for these audiences.

All this is great, but it’s also important not to swallow anything whole, and whilst Eminem’s ‘Stan’ laid out the extremes of fandom in such a way that it became a definitive term for the wrong sort of devotion, it’s worth considering that there may be downsides to dedicated fandoms from an artistic perspective.

The Dark Side of Fandom

There is a very fine line between participation and possession, and the current state of creator culture and the effort involved in servicing devoted audiences risks eliding these two things to vanishing point. The relationship between artists and their audiences is a sociological one, and it’s easy for not just our creative output but our idea of ourselves to become distorted when we gaze too deeply into the intoxicating mirror of audience regard, or chase the initial high of something going viral by trying to repeat the winning formula.

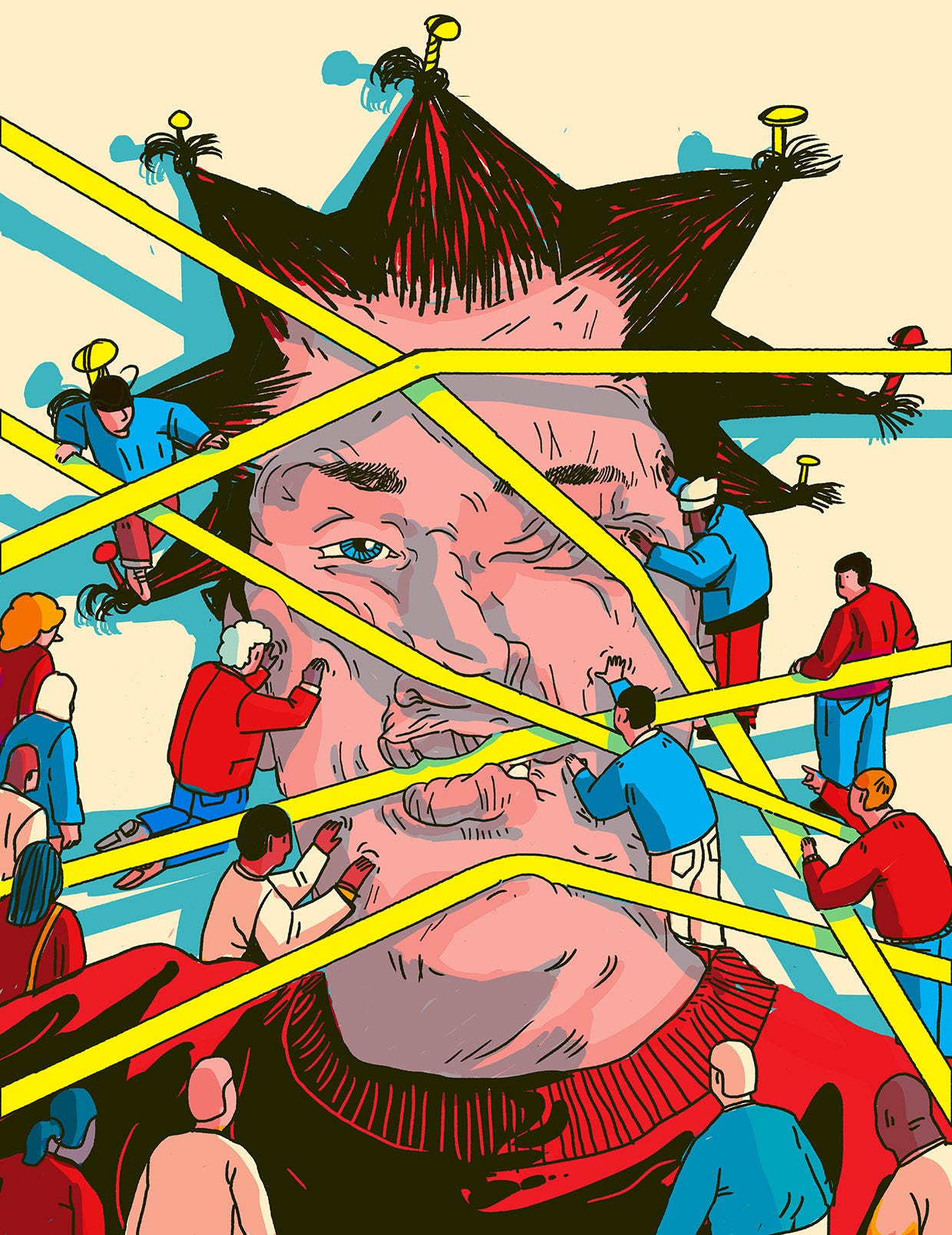

When you combine a well-defined audience with the inevitable algorithmic narrowing, the results are frightening, and it has a name: Audience Capture, which

details in spectacular fashion here. This is the process by which an artist gradually turns themselves into a caricature to keep the punters engaged. When I lived in Los Angeles, a wannabe influencer I knew once confided to me that “every time I post something that’s actually me, my follower count goes down”.Audience capture is the Faustian bargain by which we exchange integrity for reach, and surrender our creative output and ourselves to the crowd. It’s easy for those chasing fan love to end up bending themselves into unrecognisable positions from which it’s hard to recover - and this issue doesn’t just apply to art.

Fandom pursued too far is a cult

Pursued to its limits, it can lead to polarisation, caricature, creative dilution and toxic behaviour. Most recently, the New York Times’ longest-serving film critic A.O Scott, after being swarmed by fans of Marvel, Top Gun: Maverick and Everything Everywhere All At Once left the following parting shot in his valedictory essay:

“The behavior of these social media hordes represents an anti-democratic, anti-intellectual mind-set that is harmful to the cause of art and antithetical to the spirit of movies. Fan culture is rooted in conformity, obedience, group identity and mob behavior, and its rise mirrors and models the spread of intolerant, authoritarian, aggressive tendencies in our politics and our communal life.”

If our fan-based approach to art and politics are merging, we’ve got plenty of warning signals about how bad things can get on both sides of the pond - especially when politics devolves to love songs between political operators and their most engaged fans. What is the Republican Party but a few twats performers feeding the basest urges of their hardcore fans to 'shut up and play the hits' about trans rights, immigration, wokeness, etc etc rather than confronting the much larger broad-church issues that they could be addressing? The same goes for the Conservative party and Brexit, and Labour's left wing under Jeremy Corbyn. It is unlikely that Liz Truss would have felt quite so free to drive the UK's economy off a cliff if she’d been accountable to any kind of moderating middle rather than just the Conservative party faithful, as

The role of politicians is not to please a very small group of people with soundbites and red meat, it is to govern in the best interests of as broad swathe of society as possible, even if the farthest wing of each party will argue that the result is only ever dilution. Parties need moderates, the middle, the centrists, to rule well.

Within artistic and creative groups, you already know what over-serviced fans look like: an in-group of ‘true’ believers who serve as The Praetorian Guard, True Keepers of the Flame, and the bickering that results from small differences. Anyone who has ever seen a pissing contest between fans of a band about who is more devoted or was there first will have seen how this can play out. At its worst, fandom is a Girardian Triangle of Desire, where audiences get too close to creators that once would have maintained a useful distance from them. Flaubert was right when he warned that “We must not touch our idols; the gilt comes off in our hands.”

An important part of art and making culture is the license to offend and piss people off, and artists who never risk doing anything other than mirroring the values of competitive and over-devoted fans are likely to find themselves in an echo chamber very fast.

In art, creativity, and in politics too, the customer is not always right.

Looking through this lens, initiatives to build faster and stronger feedback loops into the creation of art start to look like like accelerating audience capture, and endangering the creative output too. 30 years ago, Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid made a piece of experimental art by consulting the American public, and giving them exactly what they asked for. The process was miserable for them, and the results are not going to knock any famous works out of a pantheon any time soon.

It’s easy to laugh at this, until you realise that the cinema industry is now largely driven by this dynamic, as demonstrated by the dominance of the Marvel Comics Universe Formula. Netflix is now building in mechanisms to let subscribers reshape their shows before wide release.

At what point does someone go from being inspired by their audience to a slave to them? At what point is crowd and fan interaction bad for the creative output?

The most interesting thing to happen to James Bond in a long time was the ending of ‘No Time To Die’, and that was because it was exactly the thing that no fan of the franchise would ever have allowed to happen. Bob Dylan’s folk ‘fans’ booed him off stage when he went electric, and it seems unlikely that he would have been the artist of quite the same stature if he had bent the knee to the folky fans; there were few in Radiohead’s fanbase who were asking for their left-turn from OK Computer into the Warp Records catalogue circa Kid A. Sometimes you need to give people the things that they don’t need or aren’t asking for, rather than just what they’re telling you they want more of.

These questions are important because we are already approaching a world where fans who 'know' what an artist 'should' do can brief an AI to deliver it for them without the artist ever touching, approving or condoning it.

We’ve there’s been a great deal of discussion about the role of DAOs in fuelling the next wave of creativity - but are these sort of models mediated by Discord really that useful or helpful for creative artists, or do they just constitute crowd interference?

For art and creativity to have that special quality of aliveness that differentiates brilliance from dross, it must remain unpredictable, and that means sometimes being beyond the reach of its audience’s wants.

To what extent will the creative effect of over-serving fandoms be an inexorable slide towards predictability? Is it better to be the slave of 1000 rabidly engaged fans or forever chasing the shadows of the indifference of the mass market? There are no binary or easy answers to these questions, but whatever the arguments for either side, one thing is certain: they will be written, co-written, and re-written not just by star creators, but by their audiences themselves.

WHAT TO DO WITH ALL THIS LOVE?

So, fandom and passion are the new currencies of this latest decentralising state of the internet we find ourselves in, a few thoughts on how we can harness fandom without becoming captured by it, or allowing it to ruin the careers of creators:

Don’t waste fandom - if you’ve got devoted fans, lean into them and treat them properly. It’s a terrible thing to work on a brand or business who have fans and not show them any love or appreciation.

Rethink your notions of audience. Accept that ‘serving a community’ might just as well involve speaking to an imagined audience as a real one. Your fans could be long-dead readers that you’re imagining as you create, or a group of people whose voices were never heard but whose stories demand to be told.

Get comfortable with indifference. Much of what marketers and artists do, especially in a world this crowded and attention-starved, is about over-coming disinterest, and to be honest as a strategist I enjoy working on companies and categories that no-one gives a fuck about because it’s a test of my ability to make ostensibly dull things interesting. We must not get too cosy preaching to the converted.

Harness the power of overheard conversations - strong engagement between a creator and their fans can generate enough dialogue and chatter to spill over into the indifferent and mass market.

Don’t sneer at mass. It’s become increasingly common to sneer at things that aim for and reach a mass audience, but we need these common cultural touchstones of shared meaning - the world needs more dance floors with room for both wings of the political spectrum, and we require artists that aim to reach both to create those spaces.

Don’t treat everyone like a fan, or the fans like everyone - If you are a mass brand with a smaller audience of fans, it’s important to separate what the role of fans is and how different layers of communication and activity work. Talking only to the mass market means ignoring the people who make you what you are and risking blandness; talking only to the fans risks an echo chamber.

As a final thought: probably the most important and under-rated component of any healthy fan/artist relationship is a certain amount of disrespect. We must occasionally let our idols smash themselves, to sacrifice their fanbase on the altar of artistic freedom, to free themselves from this cycle. Any ‘true’ fan will understand that their idols have the right to defy expectations. As Zadie Smith said about Joni Mitchell’s decision to put down her guitar for a paintbrush:

“We want our artists to remain as they were when we first loved them. But our artists want to move. Sometimes the battle becomes so violent that a perversion in the artist can occur: these days, Joni Mitchell thinks of herself more as a painter than as a singer. She is so allergic to the expectations of her audience that she would rather be a perfectly nice painter than a singer touched by the sublime. That kind of anxiety about audience is often read as contempt, but Mitchell’s restlessness is only the natural side-effect of her art-making…..there is simply not enough time in her life for her to be the Joni of my memory forever.6”

If you’re a fan of anything and want it to flourish, the moral may be this: if you love it, let it go.

Thanks for listening.

Economist, Why Trump Swing Voters Like Heavy Metal

Full disclosure: from the NYC office of Wieden + Kennedy, the agency I work for in London.

Drawn from the afterword to Pachinko, a book everyone should read.

Emma Smith - This Is Shakespeare

Oscar Wilde, “The Critic As Artist”

Zadie Smith, ‘Some Notes On Attunement’, in On Beauty

Sorry MJ, but I’m a super fan of this article and I’m probably the only one who really gets it.