The Verbal Web Part 2: Pay the Writer

What are words really worth? Let's play the literary lottery!

This is part 2 of a 4-part series about the future of digital writing and publishing. Read part 1 here before you begin.

Writers and football fans have a lot in common: in rational economic terms, they’re both fucking stupid.

Football1 fandom, like life-saving medical interventions and veterinary care for beloved family dogs, is almost totally price-inelastic: you can keep raising prices and fans will just keep on buying. Football clubs continue scalping supporters for insane season tickets, selling merch at absurdly marked-up prices and ripping people off under the myth of ‘love of the club’ without any dip in purchase behaviour.

But if you crunch the numbers, writers are pretty dumb too. Let’s take a look at how writing is remunerated.

Calculated against an average work week, most UK writers earn less than minimum wage .

The average salary for an author in the UK was £10,437 when decent data was last available in 2017, down 33% since 20132. They’re currently updating this survey, but it seems unlikely that a pandemic and rising living costs are likely to have writers in 2022 rolling in cash. It’s no better when it comes to advances: data from the FT in 20183 suggests that the majority of writers were seeing their advances stagnate or fall.

This is all before you get into the kind of glaring racial disparities exposed in recent cultural conversations about how a writer’s race can influence their advance and income.

In the UK authors make about 10% of what a book earns, and the other 90% goes to everyone else involved in publishing the book4. All of these numbers are ludicrous before you even consider the amount of graft that goes into producing something readable, let alone good.

As Elle Griffin has pointed out at length in her excellent Substack (#nonsponcon), there are roughly 3 million books in circulation , and only 0.02% of them sold between 10,000 and 100,000 books - which means that the odds of yours getting read are rather low.

Once you factor in volume of submissions the average agent gets deluged with, and then their chance of selling your book to the publisher, let’s review the current odds of a well-paying literary career:

This equation can be resolved mathematically in the algebraic expression WTF.

Let me offer solace in the fact that being a celebrity with a large following also does guarantee success: Billie Eilish sold only 64,000 copies of her book5 despite the fact that she has 97 million followers on Instagram and another 6 million on Twitter.

Writing is like football fandom in reverse: the market can keep paying writers less and less, and still vast numbers of talented and diligent people will pour their souls into work so poorly compensated it’s a miracle anyone with even a rudimentary grasp of probability ever picks up a pen.

I love Rebecca Solnit’s thought that to write is to hope and to hope is to gamble6 - but economically most writers have been sitting at a rigged casino table waiting for their numbers to come up and getting shafted by the house long past the moment when it’s time to walk away.

The strategy of most publishing houses is spread-betting: the hits finance the misses, which means that every author who wins a publishing deal is essentially a chip pushed out into the middle of a casino craps table. With weighted dice. And a bent dealer. And you’re blind drunk.

The fact that Fyodor Dostoevsky once wrote a novel7 about roulette to pay his gambling debts is so ludicrous, it’s enough to make a writer in 2022 run to the nearest casino with their paltry savings to try win themselves enough money to stop working and write a book.

Is it any wonder that Harlan Ellison8 was so angry?

If any of this sounds like discouragement, I come in hope, mainly because I also know the following is true:

“If you are going to be a writer there is nothing I can say to stop you; if you're not going to be a writer nothing I can say will help you.” - James Baldwin

I am betting long on books and writing, not because of favourable market conditions, but because they make my life enjoyable and meaningful. I hope/believe/know that I’m not alone in this.

Writers do it for love. Is that a good thing? Yes. Does that mean that it shouldn’t be paid properly?

All of the above is why the surge of Substack subs is promising, and why the lure of Web3 publishing is so seductive: the so-called ‘passion economy’ is meant to be a new way of rewarding how much people care about something. Writing and publishing are already a passion economy, if ‘passion’ captures the traditional Latin root of the word - as in The Passion of The Christ - which is ‘to suffer’.

Web3 publishing is interesting not because it lets writers gamble their pitiful advances on the frothy bubble of NFT speculation - but because it’s an idea that has been kicking around for more than a century in the minds of utterly brilliant creative people looking for greater ownership and control over their work.

In 1904, James Joyce attempted to finance the writing of The Dubliners by offering up-front shares in the book for £7 in exchange for a portion of future earnings9. No-one invested.

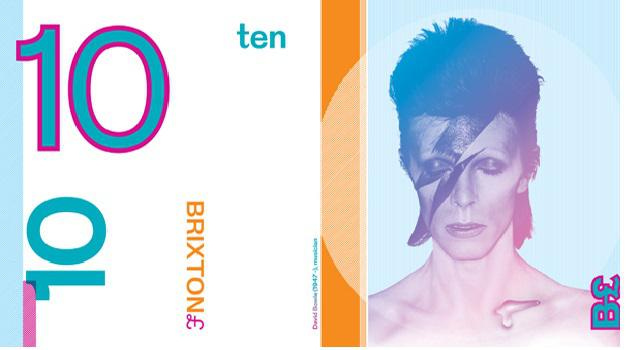

In 1997, David Bowie raised $55 million by issuing a series of Bowie Bonds secured against his work. The bonds paid 7.9 percent interest over a 10 year-long term10. The collateral was future royalties on Bowie’s music, which the bondholder felt people would continue to value. I hope they’re still redeemable given that his estate has just sold for $250 million.

In February 2016, Imogen Heap sold a song to her fans using Ethereum, as the first step in realising her vision for the broader Mycelia platform.

Emily Segal pre-funded her novel ‘Burn Alpha’ through tokens issued via Mirror, raising $75,849 in Ethereum for a novel that she hasn’t yet written and will retain a future 30% stake in.

Fantasy and science fiction author Brandon Sanderson has just bought in more than $20 million crowdfunding 4 secret novels via Kickstarter, and is now the highest-funded Kickstarter of all time.

These were all artists funding their work, cutting out the gatekeepers and connecting directly with their fans.

Whether attached to NFTs or not, it all feels less like a cynical attempt to take us all for a ride and more like an idea whose time has finally come.

If it scales, the promise of this decentralised model feels a bit like verbal pirate radio: a rewilding of the fringes of writing, a resurgence of the despoiled waste of the midlist that Amazon have flattened like some form of Cloudborne Toxic Event, and a place on the margins for challenging writing to flourish11.

A few people paying for email newsletters or literary NFTs doesn’t constitute a resurgence of a new book-buying public or culture of letters, but people enjoying and paying writers is what counts. Readers who find writing they like via Substack or Mirror are highly likely to go on and spend more money on more writing elsewhere if they’re not already doing so.

So far we’re seeing established literary novelists use Substack to connect with new readers, but I hope that in the next year or so we might start to see writers that have built up readerships via digital reading platforms being sought out by agents and publishers, as these kind of audiences are far more likely to be convertible into real books sold than passive followers on Instagram or Tiktok.

It’s already been discussed that this is moving us towards a patron model or Kevin Kelly’s 1000 True Fans idea, where people with their own audiences can get a writer funded and published.

(In the worst-case-scenario, it means that anyone and everyone will be able to pay broke writers to pen hagiographic biographies making them look like a less shitty person in retrospect, but every new tech comes with worrying potential rebound effects).

Initiatives like Ghost Knowledge mean that anyone with a topic and some taste can effectively turn themselves into a commissioning editor: pitching a writer and theme, funding it, and bringing an audience along for the ride to enjoy the results.

Taken to its extreme, we could even see particularly successful writers seek to become vertically-integrated ‘direct-to-consumer’ publishers, not only creating their own work but commissioning, editing and publishing other writers.

Musicians have their own labels and streaming platforms, film-makers have their own production companies, Hideo Kojima has his own gaming studio. Kanye West even released his latest album through a smoke alarm stem player to cut out the middle man: wouldn’t it be nice to see some writers seize control of the means of production too?

If 20% of the writers bring in 80% of the revenue for a publishing house, it stands to reason that a bigger-name writer might want more creative and editorial control over what writing their success is funding.

However the funding happens, in the crowded attention economy, dedicated platforms for good quality and easily-accessible writing to compete for attention can only be a good thing. It allows writers to be paid for the quality of their work, rather than its ability to attract attention to be directed elsewhere for advertising purposes.

It’s easy, in the case of Mirror and NFT/crypto-funded writing, to say that it’s all based on digital currencies that don’t exist and are pinned to no real underlying asset - and these concerns are entirely legitimate, especially in the wake of market moves wiping $1.4 trillion off the total value of crypto.

As Cory Doctorow has pointed out, the idea is useful but the market is stupid.

Even fierce critics of the aesthetic and intellectual poverty of much of what is winning huge sale prices in the Web3 era admit that NFTs might be very useful when applied to publishing and getting writers funded. What many find most repellent about the current NFT bubble - its rampant commerciality - could prove to be a feature not a bug when it comes to publishing, because it will act as a counterweight to a culture that treats words and writers as cheap, if not near-worthless12.

The speculation distracts from the fact that much of the creative potential of NFTs lie in how they might strengthen the relationship between writer and fans. In publishing, this could become a digital version of spotting someone on the train reading the same book as you or carrying a tote bag from a bookshop you like - a way of like-minded people connecting across the crowded room of the Internet.

Long-term, there should be plenty of opportunity for blended purchases of combination digital-and-physical literature: Alexander McQueen is selling physical shirts with NFT tokens attached that give you blockchain ownership of a digital garment as well (although they’re not inter-operable with any digital environment where you might want to be seen wearing virtual McQueen threads).

Now imagine a writer selling a signed version of their physical book via The Folio Society, with a complimentary digital version featuring limited-edition artwork by a famous illustrator, with an NFT as proof of authenticity and scarcity.

To me, it feels like the more things like Substack and NFT-financed writing on Mirror become a means of funding this kind of creativity and community, rather than Ponzi-scheme behaviour, the more real their value becomes. Maybe we’ll only really grasp the potential of this current moment when the idle speculators have gone home and only the devoted readers and patrons and writers are left.

So yes, it’s all a bit nuts, but it’s also exciting to think of new ways of acknowledging the value of writing and rewarding writers. It suggests a restored sense of the craft as value-creation.

Somewhere, I like to imagine the digital ghost of Harlan Elisson, laughing his arse off and nodding approvingly.

So, this chapter has mostly been about the $£€¥, but there’s much more to The Verbal Web than questionable economics. These new behaviours aren’t just changing how writers get paid, they’re also stretching the cultural boundaries of how writing gets done and who gets credit for it.

Join me next time for a look at how The Verbal Web is reshaping our ideals of writing being the work of a solitary author, and reducing the emotional turbulence of one of the world’s loneliest jobs.

And once again, thanks for reading.

For my thousands of American readers: soccerball.

Authors Licensing and Collecting Society, 2018 Author’s Earnings Survey, UK

https://www.ft.com/content/5c7c31b8-82e3-11e9-a7f0-77d3101896ec

https://www.alcs.co.uk/news/are-authors-an-endangered-species

Source: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/07/books/social-media-following-book-publishing.html

Rebecca Solnit - Hope In the Dark

No, I’m not making this up. The Gambler is worth a read, just about.

He also once mailed a publisher 215 bricks postage-due because they wouldn’t pay him properly, and said “I won’t take a piss unless I’m paid properly’.

Source: James Joyce by Richard Ellman, via Jeet Heer’s Twitter account.

Scott Galloway, https://www.profgalloway.com/scarcity-cred/

Whatever your views on cancel culture and which side of the political spectrum is more likely to censor books, it’s much harder (if not impossible) to censor one which has been funded directly by 1000 dedicated fans than one that needs to sell 5,000 or 10,000 copies to earn out its advance and not be a failed bet for a large publisher - and so is likely to be defanged by an editorial team trying to meet the needs of a highly sensitive (and possibly imaginary) mass market reader.

A more cynical fallback position from here, argumentatively, might be that even if we are in a speculative asset bubble, that it might be nice to see some of that value being redirected into art and creativity and writing.