The Verbal Web Part 3 - The World's Loneliest Craft

We're all just looking for someone to write with

This is part 3 of a 4-part series about the future of digital writing and publishing. Read parts 1 and 2 before you begin.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a writer in possession of a draft must also be in want of some friends.

Bands have live crowds, theatrical artists have their audience in the stalls, film-makers have entire shoot crews and cinema audiences. Writers have the long and solitary work of banging out words in a way that can often feel like pissing into the void.

The acknowledgements pages of novels are usually long and crowded because writing them is the Marathon Des Sables of creative pursuits - an insane and punishing endeavour whose rational appeal you may struggle to explain to other human beings not suffering from the same affliction. Having a fellow pack or runner to go alongside you at least some of the way reduces your chance of bombing out or giving up because you can no longer put one word after the other.

Part of the issue is that writing is inherently a low-feedback task: it’s often just hard to find people to read and comment on your work, and it can take a lifetime for fiction writers to find a handful of trusted first readers.

As as rather famous scribe put it:

“Writing is a lonely job. Having someone who believes in you makes a lot if difference. They don’t have to makes speeches. Just believing is usually enough.”

I’ve already talked about how The Verbal Web might lead to a world where we value and remunerate writers better, but one of the other features of this new ethos is how it seems to offer an alternative to this kind of solitary literary loneliness.

All of these platforms that I’ve mentioned - Foster, Substack, Mirror - have placed community at the heart of how writing gets done and consumed. They also come with attendant Discord groups where people can exchange ideas, pitches, writing and other material in nascent form. You can get feedback and, in my case, find out how shit their ideas and/or writing are at an early stage.

To some, this might sound like early ideas being snuffed out in their infancy, but it can also save you the year of graft, two drafts and small fortune in self-esteem required to learn that your novel idea is a non-starter.

Right now, thousands of writers are still engaging with George Saunders’ Story Club, and one of the most heart-warming things about the whole affair is just the sheer sense of enjoyment of one another’s company that you find on the message boards. These are people connecting with like-minded people, and in some ways the knowledge about the craft of Russian Short stories being acquired is almost secondary. The BBC is about to do something similar with Alan Moore’s storytelling course1.

Through their Grow scholarships, writing hours, and other initiatives Substack are displaying a deep understanding of what makes writers tick, stops them writing and can make their job less difficult.

It used to be that one of the only ways for writers to find their people and get this kind of sounding board and support was by signing up for a prohibitively expensive MFA or course, but it has often felt to me that these are partly a means of farming the dreams and loneliness of writers for money.

(And they also come with their own issues in terms of the type of writing they turn out, as Erik Hoel has pointed out rather cogently).

It’s too soon to say, but it feels like this moment in online writing is creating sub-cultural pockets of writers gathering around tiny digital campfires, sharing early ideas and supporting one another.

So sure, ‘no man is an island,’ etc - but the emotional support they offer is only a small part of it.

These things are exciting not just because we all need to be a bit less lonely, or find people with similar intellectual interests to befriend and maybe have sex with.

Whilst rewarding writers properly and soothing their sense of loneliness is important, it also offers a different cultural narrative about how great writing gets done. Consider the following:

Gertrude Stein’s Salon, and the literary rivalry of Hemingway and Fitzgerald.

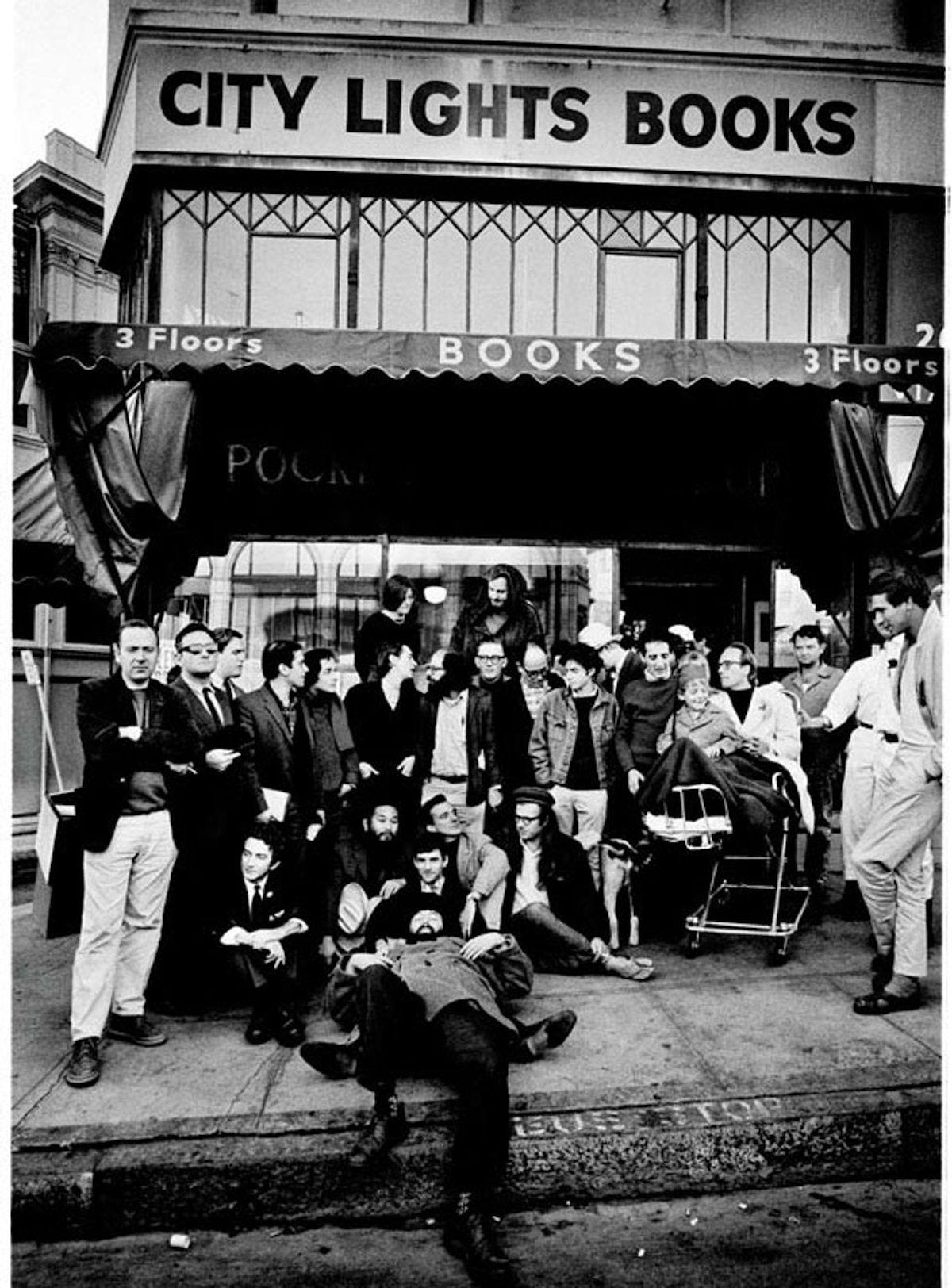

Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, The Beats and Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights Bookshop in San Francisco.

Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston and The Harlem Renaissance.

Virginia Woolf and The Bloomsbury Set (they weren’t just sharing writing, they were also all fucking each other. It was like Substack and Tinder rolled into one!2).

Pre-War Vienna and “The Age of Insight”, where in the cafe society of Vienna the likes of Freud, Jung, Klimt, Schiele, Ernst Mach, and other insanely brilliant scientists, artists and creators hung around to exchange ideas.

Although individual writers get the plaudits, great writing often come out of scenes and crowds.

Brian Eno famously referred to this as ‘scenius’

to capture the idea of communal genius, or network effects in creativity and thinking3. More recently, Steven Johnson explored the way that thinking recombines and evolves in these scenes as the expansion of ‘the adjacent possible’4.

We see the fully-formed texts, but never the immeasurable swirl of conversations, arguments, half-formed ideas and relationships that often feed into it.

Our current technology and platforms are now catching up with a truth several thousands of years old, and one that Maria Popova has been making in her Marginalian project for quite some time: writing is the original internet.

Of course, the kind of community incubators I’m referencing above are once-in-a-generation things that are impossible to plan or to control - a new curriculum of Progress Studies is being proposed to try and figure out how you stimulate them - but the current spirit of online writing could act as a petri dish that might increase the chances of germinating some new scenes, and new types of writing too.

More ways for writers to collaborate = more unusual types of writing

I left one scene out of my earlier list, and that’s because it’s the one that probably has the most bearing on where this new wave of The Verbal Web is likely to push us.

The Oulipo - Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle, roughly translated as "workshop of potential literature" - were a group of radically experimental French writers and mathematicians using formal constraints to power new creativity in writing.

They were fond of inventing new games or experimental demands that would drive their verbal and narrative creativity to new heights through limitations.

Notable works that came out of this school of writing include Raymond Quenneau’s Exercises in Style, where he retells the same anecdote in ninety-nine different styles just to prove the point that it’s not the story, it’s the way you tell it5.

Their poster-boy was Georges Perec, who once wrote an entire book without using the letter E, and also wrote one of my favourite novels of all time, Life: A User’s Manual.

The book is a formal game or puzzle with a series of borderline insane self-imposed limitations: the apartment block is arranged like a chess board, the narrative moves around the building like a Knight on the board, and each room in the apartment is populated with lists of objects using a Graeco-Latin bi-square.

If this makes it sound like an exercise in showing off, it’s also as life-affirming as it is dazzling. Literature, in the way that The Oulipo approached it, was somewhere between a craft and a game.

Their playful collaboration was an engine for their creativity, and I hope that a new era of internet writing might foster a similar spirit given this kind of collaboration can happen more easily, more widely, and faster.

In the new ways that writers are starting to play around with community, form and platform online, it feels like we might be approaching a similar ethos.

When I see The VerseVerse experimenting with how poetry, art and technology come together to create new narrative and verbal work, or Soltype are creating a platform for communities to support literary output via NFTs, I get excited about what happens next.

Not all of this conforms to what might be termed self-consciously ‘literary’ output, and is much the better for it. Perhaps the most interesting part of this changing moment is the new forms that this collaborative spirit of these new platforms might create.

So, a few questions to think about for the final piece in this series:

What new writing scenes or groups or communities are we going to see combine to create stylistic cross-breeds between radically different types of writing?

What new ways of expanding the idea of voice might we get from writing communities connected in real time as they work, where polyphony is more natural than monophony?

What new formal or genre experimentations are going to arise out of a writing ethos of collaboration and community, rather than isolation and individuality?

What new literary forms might tap into the potential of new platforms for reading like Mirror, Channel, or Substack?

Join me next time as we delve into the best bit of all of this: how the next chapter of The Verbal Web has the potential to explode the way that we think about the concept of literary voice.

Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you next time.

Yes, I’m going to sign up, and so should you.

If you read this and decide to pitch this product idea to a VC for a large chunk of seed money, I will take my IP cut at 15% or more.

Source: https://www.wired.com/2008/06/scenius-or-comm/

Steven Johnson - Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation

See also: The Aristocrats joke.