In December 2021, Booker-Prize-winning writer George Saunders announce that he would be teaching his latest course on the short story via an unusual medium: email.

Several times a month, in a fashion familiar to anyone who’s read his book “A Swim in the Pond in The Rain” about the Great Russian Short Story, he turns up in your inbox and teaches a lesson. He does it in a way that’s inseparable from deep appreciation, and also comments on threads from readers, sprinkles encouragement on anyone whose motivation or self-belief is flagging, and posts pictures of the ponytail he grew during lockdown.

His students now number in the thousands, and the community is a mixture of writing group, fan club, confessional, and penpal programme. It will, no doubt, inspire hundreds of thousands of words, create new friendships, and birth plenty of quality short stories.

To be clear: right now, a world-famous author is giving away the wisdom of his craft accumulated over a lifetime of writing to anyone willing to listen for $6 a month via email.

The value of the MFA course he teaches at Syracuse takes about 5 or 6 students a year, and its course value is pegged at around $17,000. I have no idea how the revenue from Substack compares to what he makes from each book he sells, or the regular teaching post he’s held for two decades, but dwelling on the economic value of all of it would be an exercise in missing the point1.

In making such inaccessible teaching so widely available, St George2 also models a new direction and set of behaviours for an industry that can often feel like one of the world’s most closed-off: publishing.

It is sometimes easier to imagine the end of publishing than it is to imagine the end of reading, or writing

In my own brief experience, rejection by interaction with the publishing industry has felt like banging my head on the polished hardwood door of a very old private member’s club, and the economics of making a living by writing novels in 2022 seem ludicrous when balanced against the labour needed to write a good one.

I’ve got plenty of distance left in my literary apprenticeship - my experience thus far amounts to one short-story prize win, an agonising brush with a publishing deal for a debut novel, and a lot of backlogged material I will soon be casting into the open arms of the internet via this Substack - but exposure to publishing thus far has left me with the creeping suspicion I’m busting a gut to join a guild of artisans of a dying craft.

Yet the clearer it is that writing is largely devoid of any rational economic benefits, the more keen I am to do it - because I love it, and anyone paying me for such a thing would be a phenomenal bonus. Still, no-one wants to queue for ages to get into the club to find that the dance floor has emptied and the DJ has packed up and fucked off.

So whilst this all might sound like a digital poison-pen letter or bitterness turned into ink, I come to praise publishing, not to bury it, and pen this in the spirit most natural for writers: hope.

Change is in the air, and out on the fringes of the industry we’re being given glimpses of how it might evolve to benefit both writers and readers.

As Benedict Evans recently observed3, ‘everything that the internet did to music or newspapers is now happening to everyone else’, and it’s probably high time that publishing either surfed this wave or was held down by it until it stopped kicking.

Being a writer right now feels less like a heroic but failed rearguard action against the stampeding forces of the modern attention economy - being trampled underfoot by TikTok, Fortnite and VR - and more like an area of culture that’s been given a very welcome shot of electricity.

Consider the following:

Substack cleared a million paid subscriptions in November 20214, and chances are that Xmas gifting probably boosted that some more. For reference, this million subscriber mark was reached in exactly the same month by the Guardian5, one of the world’s most respected publishers, only after six years of its voluntary subscription programme.

Substack has created paying readers on writing about topics as diverse as under-appreciated 80s cinema, the perils of modern dating and rare items of clothing6. In addition, established writers like Salman Rushdie and Chuck Pahluniak are publishing novels and short stories directly to their readers, alongside comic writers like Grant Morrison. This is funnelling fresh money into a new ecosystem of writing, with most of the proceeds going direct to the talent creating the work.

The media behind this resurgence - email - has been around for more than half a century, is digital communication’s version of the cockroach, and was probably the last anyone would choose as the standard-bearer for a new reading culture.

On Foster, a community of writers is pitching, editing and co-writing one another’s work, and discovering in doing so that writing is better and less lonely when done together7.

Meanwhile, over on Mirror, people are experimenting with radical new ways of publishing, creating and funding writing8, including using NFTs9.

Emily Segal pre-funded her novel ‘Burn Alpha’ through tokens issued via Mirror, raising $75,849 in Ethereum for a novel that she hasn’t yet written and will retain a future 30% stake in.

Mario Gabriele enabled readers to crowdfund an illustrated Generalist essay, raising about $62,000 in Ethereum.

Packy McCormick’s “Power to the Person” essay shared proceeds with everyone that he quoted in the essay via blockchain publishing, modelling a new way to not only tip the hat to those that have influenced you, but also to put a tip in the hat.

The Chain Tale is a collaborative writing project where each owner of the NFT gets to write the next chapter of an ever-extending story.

The New Fiction Society, in partnership with Neil Strauss, are releasing his next book “Survive All Apocalypses” as an NFT you can read: the catch is that one owner of the NFT, drawn at random, will also gain (partial) copyright to the book and go from being a reader to a publisher.

Collectives like The VerseVerse are publishing NFT work created by collaborations between poets, artists and AI.

Now, it could be that all of this kind of experimental behaviour has existed since Wordpress and Medium, and like some colonial-era explorer ‘discovering’ a place that’s been inhabited for thousands of years, I am only arriving late and stating the f*cking obvious - but something novel and exciting appears to be going on.

Just in case anyone accuses me of blind optimism about new tech, I should point out that someone just paid €2.6 million for the NFT of concept art for Jodorowsky’s unmade Dune movie that they don’t own any IP rights to, and Moxie Marlinspike recently sold an NFT artwork that transforms into the turd emoji when you view it.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” etc.

It’s too easy in these moments to over-read the tea leaves and declare some sort of seminal shift is happening. Already this moment is being compared to being in Venice during The Renaissance, a historical comparison that I heard approximately once every ten minutes from people in and around Silicon Valley when I lived in California10.

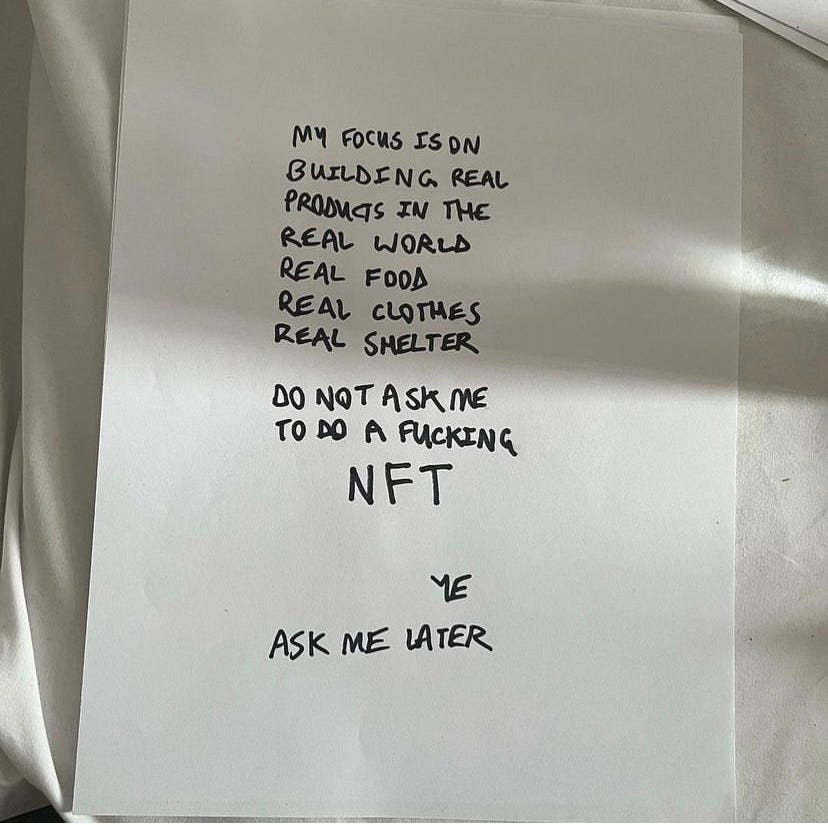

When it comes to NFTs and writing, the rampant boosterism often on show on platforms and Discord servers may be reflective of genuine excitement about digital writing, but it’s also enough to make even a starry-eyed optimist pause.

I remain highly suspicious of such evangelism, not least because recent examples involving WeWork and Theranos suggest that bullshit is built into the tech hype and investment cycle. A useful response to the sweeping promises around Web3 is always one of cautious and sceptical optimism, best summed up as11:

I fear the geeks even when they come bearing gifts

It’s too early to know whether the NFTs people are buying are future digital memorials to our generation’s South Sea Bubble or Tulip Fever, except with a Bored Ape standing in for satire from Swift and Hogarth - but what is happening with digital writing is not just about the fate of Web 3 and NFTs.

The numbers we’re talking about right now around these behaviours on Substack and Mirror are not anywhere near close to what tech companies or venture capital firms might call ‘scale’ - at 250-350 million users console gaming is still considered ‘small’ in tech terms. Equally, I’m not sure the total writing & reader communities12 of Foster, Mirror or Substack are enough to keep anyone at a major publisher up at night given that book sales had a good pandemic and continue to rise in both the UK13 and US14.

But they represent a growing vanguard of new literary behaviour which, if it touches the mainstream, could change the way we read and write in some interesting and fundamental ways.

At their most exciting, they offer a glimpse of a cultural and commercial shift in our notion of writing - and because sometimes giving such moments a name can gently fan a spark, let’s indulge ourselves and do so:

THE VERBAL WEB

It offers us a chance to demolish some long-held cultural and commercial notions of how writing happens, what words are worth, and what it means to be a writer - to shift away from popular conceptions of writing as lonely, exclusive, and poorly remunerated to the promise of a more inclusive, collaborative and better-paid internet for writers and readers.

It could change how writers get paid, how we feel, and what we write, hopefully for the good.

Over the next few posts, I’m going to be digging into the creative, community and commercial potential of these new platforms for writers, and hopefully sharing something useful along the way.

And whilst it’s not all about the money, the money is a big and important part of it.

So let’s take the advice of famed Watergate political operative Deepthroat, and ‘follow the money’ - join me next time as we head down the rabbithole and delve into the questionable economics of writing, the mind-bending ways that people are trying to earn a living from their craft, and the new possibilities of The Verbal Web.

Thanks for reading15, and hopefully I’ll see you for the next chapter.

Also, being George Saunders, he has of course set up scholarships that people can pay for through Substack so that people can fund other writers. What a guy.

Pope Francis, if you’re reading this, let’s talk.

Source: Benedict Evans, “Three Steps To The Future”, December 2021

Source: on.substack.com/p/one-million-strong

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/gnm-press-office/2021/dec/14/the-guardian-reaches-one-million-digital-subscriptions-milestone#:~:text=At%20the%20end%20of%20November,180%20countries%20around%20the%20world.

The literary equivalent of a financial disclosure: I am a paying subscriber to Story Club, and a non-paying member of Blackbird Spyplane, The Common Reader, Salman’s Sea of Stories, Astral Codex Ten, The New Cue, The Insight, The Novelleist, The Snapforward, Trapital, Terra Nullius, and Wonder Cabinet.

With thanks to the Fosterati who contributed to this.

With thanks to David Phelps for drawing these examples together on Twitter - go check out his newsletter at davidphelps.substack.com for more of these knowledge bombs.

If this is the first time you’ve heard about NFTs, CONGRATULATIONS! You are one step along on the road to enlightenment which includes discovering that at least 50% of Web3 is actually just content explaining what Web3 and NFTs are. If this explanation isn’t helpful, I suggest starting here: https://www.theverge.com/22310188/nft-explainer-what-is-blockchain-crypto-art-faq

I think this historical comparison expresses the desire of people working in tech to believe they are doing work of creative and societal importance as well as commercial reward. It provides a soothing sense of impact and perpetuity, whilst dodging some of the unpleasant historical parallels that might come with stating that they are, say, Rome or Victorian Britain at the height of their empires. It is also a topic for a separate article whether there was more human shit in the streets of Renaissance Venice or Frisco in 2022.

I don’t consider geek an insult and I don’t think of everyone who works in tech as a geek, but I’ve been looking for an excuse to use this aphorism for a while and so here we are.

Important note: reader and writer communities, not user bases.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/jan/11/uk-book-sales-in-2021-highest-in-a-decade, drawing from Nielsen Bookscan data

https://www.statista.com/statistics/422595/print-book-sales-usa/

I have also published this on Mirror and this draft received input from the Foster community as well.

Great piece. Loved the research and analysis. Will wait for the next issue.