When Stanley Kubrick was shooting Full Metal Jacket, he turned Beckton Gasworks into a battlefield in Vietnam

This involved lots of meticulous and seemingly pointless set dressing, including him ramming prop rifles into the mud far away from where any of his shots would be taken. When one of his crew members asked why he would bother dressing a section of the set that wouldn’t even make it into the film, his response was simple:

‘The actors can feel it’

I first read this anecdote at The Design Museum’s excellent Kubrick Retrospective a few years back, and the rest of the exhibition was just one example after another of his near-maniacal devotion to making great cinema: my personal favourite was the copy-written manual for the zero gravity toilet in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

What kind of maniac would bother crafting fifty lines’ worth of manual for a toilet prop that’s only in the film for a few seconds, and which no-one can read? Precisely the sort of person that would make a film like 2001: A Space Odyssey. Kubrick referred to his role as a director as ‘a sort of ideas and taste machine’, and his dedication to his craft was visible in everything from the vast scripts for the Napoleon film he never made, to his rejection notes for poster concepts from one of the greatest designers of his era, Saul Bass.

He would never duck the hard labour required to elevate something to the truly spectacular: when he was brought on-board to direct Spartacus, he read the script and pointed out to the studio that they had contrived to write a film about a gladiator revolt that had no battle scene in it - presumably, because those were the most costly and difficult spectacles to create. They might have been easy to justify removing for studio execs more worried about money than art, but not for a man with a seemingly endless tolerance for difficulty in the pursuit of cinematic brilliance. The rest is history.

Kubrick once said, when talking about what makes a film great, that it needed only two things:

“Truth", the thing that touches you, the thing that you connect with; and “spectacle”. It must grab you by the throat and make you want to watch.

It makes you wonder what he would have thought about generative AI.

Deathmatch: Stanley vs Sora

The array of generative AI tools and the escalating power of what they can do with just a few prompts is increasing exponentially - and it’s made many creative people stare hard at the nature of what they do and ask some difficult questions. The first casualties were writers, many of whom have spent the last year asking themselves what special status their craft deserves when a machine can conjure plausible consciousness out of text.

And now, after the initial deluge of shitty Midjourney comps and crappy video output, we’re starting to see things like Sora, Genie and Runway show where these tools are going to go, with impressive text-to-video production the latest development.

Say what you like about them, but they are a step up in terms of craft, and they don’t look shit. Even if they aren’t subject to Moore’s Law, the creative capability of these things is likely to accelerate.

But in much of the breathless discussion about these generative tools, there seems to be a singular theme: you have only to conceive of something and speak it aloud, and it will do the realising for you.

In the era of AI, we're promised that many forms of creativity will become incredibly frictionless and fluid to realise. They will reduce the drag of creativity, the speed with which you can go from imagining something to realising it, to almost zero. In this model, creativity is merely imagination, and the laborious bringing of any idea to life is an unfortunate bug that any sane creator would automate away given half the chance. Hey presto, we automated the difficult making part! Let the AI Artistic Renaissance begin!

The problem with all of this, of course, is that it totally misunderstands how creativity works.

Making creativity easier won’t always make it better

Creative craft is not the laborious tax needed to bring the pristine imaginary into being - it’s a form of embodied thinking in and of itself. Craft is the way that any idea moves from its original conception onto higher ground that its maker may not have even seen until they set to work. Many writers know, or at least have faith in the notion, that they do not know what they think until they sit and begin to write.

‘A writer is one to whom writing comes harder than anyone else’ - Thomas Mann

In crafting an idea via words, instrument, or hammer and chisel, its maker will meet its limitations and its hidden depths, and be able to examine it from fresh angles. It no longer lives as something pristine and untouchable in their heads, but becomes real. Bands find new versions of their songs live, sculptors don’t always know what they are making until it emerges. In revising the work we are shaping it and re-imagining it.

As the storm in a teacup imbroglio over the Apple iPad Crush ad exposed, we fear something being lost when we cede the making of our ideas to a machine that doesn’t ask as much of us as we give to it. Carrying a camera doesn’t just capture the world, it’s a means of devoting better attention to it: many tools are Borgmann’s ‘focal objects’, things that deepen and strengthen our relationship with our ideas and the world as we use them, rather than shallow them out1.

Of course imagination matters, but most creative work is not just about ideas, but a form of embodied thinking. William Blake wasn't just a visionary poet, writer and painter, he was someone who learned to use a printing press and etch: these craft skills had considerable influence on the type of art that he made, and doubtless changed his vision as he started to execute it. Treating the craft of an idea as a secondary process that should be automated away reduces the thinking itself, not just the realisation of that thinking.

The truth about unconscious processes is that the book can know more than the writer knows, a knowing that comes in part from the body, rising up from a preverbal, rhythmic, motor place in the self - Siri Hustvedt, Living Thinking Knowing

Without succumbing to the bullshit mysticism that plagues so much dialogue about creativity, it’s possible for craftspeople to have creative competence without comprehension2 - many might not even really know what their idea is before they start to make it, and so skipping from imagining it to an AI-realised version of it amputates a huge swathe of making where the magic really occurs. This part of the process is difficult because it is valuable.

Creativity is 80% Idea & 80% Execution

This aphorism from UK advertising legend Sir John Hegarty has a great deal of truth to it. Many ideas sound fucking stupid when you strip them back to just their conceptual core without any of the craft, style and execution that makes them special.

Sound pretty dull, don’t they? In executing them, their makers elevate them too.

I should state at this point that I’m not a luddite, not someone hankering for some bucolic pre-technological era of analogue beauty. Technologies have always changed both the process and output of creative work in good and bad ways. Tools from Photoshop, digital cameras, After-Effects, fucking Autotune and many others have not even made creativity faster and easier, they’ve also triggered entirely new forms and innovations within the fields that they’ve touched.

I am tinkering with a few AI tools in my strategy work (although I don’t want an AI to do my writing for me). It seems obvious that many of these tools will make it quicker and easier to go from zero to one in creative work - they let you sketch out new ideas much faster. It is already the case that the process of prompting and coaxing output out of AI tools is a form of call-and-response process in and of itself, and perhaps eventually a type of craft too.

And as game designer Tim Soret has pointed out, perhaps the most interesting thing AI tools offer is the ability to prototype or proof-of-concept an idea quicker, in order to pitch it and unlock the investment, time and talent to craft it to its true potential. But there’s a big difference between accelerating an artistic process and negating it, and as Neal Stephenson suggested in a recent interview3:

It seems like one of the first applications of any new technology is making things even shittier for artists. That’s certainly happened with music

Aside from the economic impact of these tools and how they will be used to squeeze creators to do more for less, they do raise a simple but hard-to-swallow truth: creating highly original, distinctive and striking output requires going to places, figuratively and literally, that others cannot. AI tools place within easy grasp huge swathes of creativity that might once have been out of reach - but they allow us to colonise the more obvious and immediate territory on the map of our imagination, rather than scale its most difficult mountains. They will get us from 0 to 1, but not from 1-100. And those 0-1s are increasingly what we see online.

The Era of Spectacle Without Truth

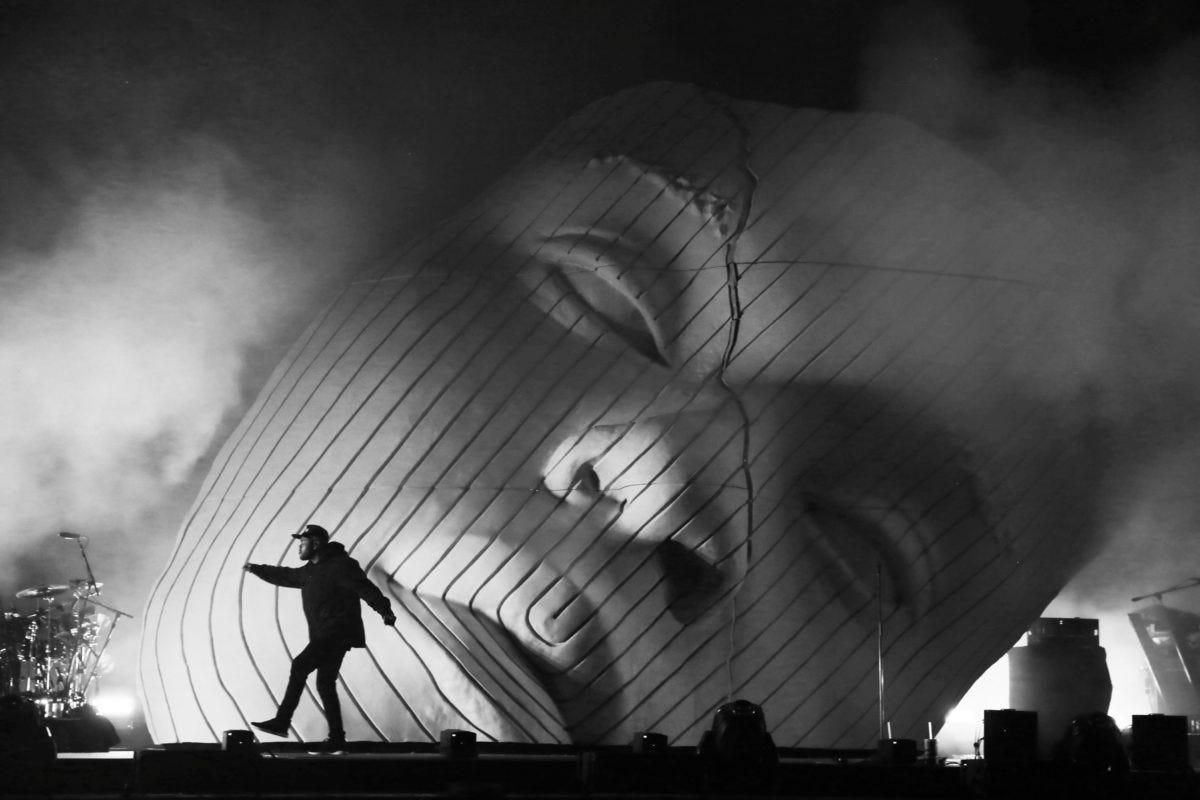

As evidence: the internet is already awash with innumerable examples of 'real-life' events that are AI overlays onto reality supposedly filmed by bystanders: the Jacquemus Bags, North Face putting a puffer jacket on Big Ben, and various others. It’s easier than ever to produce the sort of low-latency ‘moments’ that pop up briefly online and then vanish as soon as someone notices that they're fake - they’re an empty-calorie dilution of the spectacular. Or, to borrow Kubrick’s frame: spectacle, minus the truth. The ancient Romans had a name for it: Prelusio, the pantomime warm-ups that took place before real gladiatorial combat, which no-one cared about because they were obviously fake in comparison to the blood, sweat and death of the real thing4. As I’ve argued elsewhere, these empty spectacles aren’t a replacement for the visceral impact of an Es-Devlin-crafted live show, or someone putting craft and energy into anything really hard delivered at scale.

Red Bull Stratos would have been much less impressive if they hadn’t actually done the work to take Felix Baumgartner to the edge of space. For everyone involved it was brutally hard - which is exactly why it was so impressive.

Sometimes magic is just someone spending more time on something than anyone else might reasonably expect - Penn and Teller

It’s not hard to detect an emergent church/state split around this when it comes to how artists approach the things they make: the recent Hollywood Writer’s Strike gave us a clear indication of where the inclinations of some of the world’s best creators lie, and it’s a question of process as well of price. If you’ve spent the last thirty years of your life honing your voice like an instrument, it’s justifiable to feel aggrieved that your practice and pay has been replaced by a vocal sampling tool trained to sound exactly like you. But someone like Christopher Nolan is so defiantly analogue that he doesn’t just shoot using film, he’s also reported to use a flip phone, avoids social media, deliver scripts to writers via print-outs and work on a computer with no internet connection. It’s worth considering that this philosophy is not just a cute stance but somehow essential to the spectacular quality of the films that he makes. If you’re constantly worrying about how many likes your latest post had or have had your visual diet polluted with garbage from Midjourney, can you envisage scenes like this?

Whilst everyone worries about losing their jobs, it does make me wonder if we might start to see some sort of ‘human premium’ return when it comes to creativity and how people value it. Doing many types of creative work is going to get quicker and easier, but there are some outputs for which the old methods are not only trusted, but also hard to beat in terms of their quality. William Baumol, the economist who named The Baumol Effect in 1965, pointed out that wages in the performing arts continued to grow because some things were not improvable, stating that ‘The output per man-hour of a violinist playing a Schubert quartet in a standard concert hall is relatively fixed’, and yet their wages had continued to rise5. People were still willing to spend on the arts even as prices rose and so artists could continue to command their value.

So what would Stanley have thought about AI?

Alas, it’s a split jury. When asked, the person I know who’s looked deepest into Kubrick’s work6 pointed out that Stanley was more than willing to try out anything that would make his films better. He said that if it could be written or thought, it could be filmed, and it seems unlikely that he wouldn’t at least have considered any new tool, generative or otherwise, that might have helped with that. But Kubrick was also afraid of flying, and as Dr Strangelove and 2001 suggest, justifiably a little frightened of other new technologies like AI and nuclear weapons.

So we cannot ask Saint Stanley to rise from the grave and decide for us. But beyond what creators can get paid for their work, it remains to be seen whether automating away some of the craft of realising an idea also removes the point of view and emotional voltage that is the most important thing any human brings to their work. We need both the truth and the spectacle: in any form of creative work, for someone to touch or move an audience, they need to have been moved themselves first. We might not know exactly how or why, but we sense the human being behind it.

So next time you’re facing the laborious task of making something and find yourself tempted by new tools that promise to automate away the hard part, remember this: the care and struggle that goes into bringing your idea to life is precisely what, when people encounter it for the first time, will make them feel something.

‘Things men have made with wakened hand and put soft light into, are awake through years with transferred touch and go on glowing for long years. And for this reason some old things are lovely, warm still with the life of forgotten men who made them.‘ - D.H. Lawrence

Daniel Dennett: From Bacteria to Bach and Back - The Evolution of Minds

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2024/02/chatbots-ai-neal-stephenson-diamond-age/677364/

Robert Schiller: Narrative Economics - How Stories Go Viral & Drive Major Events

https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/05/23/what-would-humans-do-in-a-world-of-super-ai

Courtesy of my friend & director James Gallagher, whom I owe a great deal of thanks for his help on this piece.